Today’s post was written by Bruce Waters, former educator at the McLaughlin Planetarium and founder of the Killarney Provincial Park Observatory.

Midafternoon this April 8, one of the rarest events in the universe will occur for observers in Southern Ontario: a total solar eclipse!

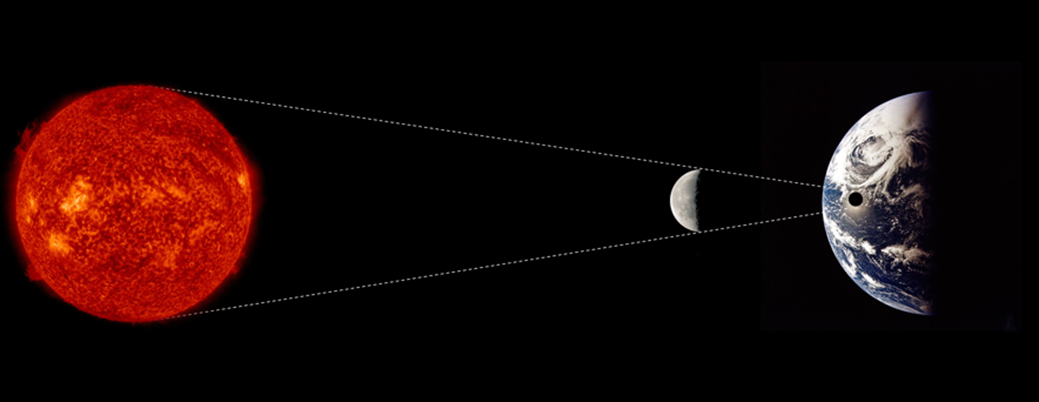

A total solar eclipse occurs when the moon blocks the light of the sun completely for a duration of seconds to several minutes.

This extremely rare event — the last one viewable from the GTA area was in 1925! — occurs nowhere else in our solar system and, although statistically unlikely, may not occur anywhere else in the universe.

In fact, in another few million years, it won’t be seen quite the same way here, as the moon is slowly moving away from the Earth.

Let’s learn about this year’s total solar eclipse!

**If the eclipse will overlap with a visit to parks, please refer to this blog.**

There are three primary phases to a total solar eclipse:

- Initial partial phases, where the moon begins to block the light of the sun

- Totality, when the sun is completely obscured by the moon

- Final partial phases, where the moon departs away from the sun, exposing more and more of the sun itself

Initial partial phases

During the initial part of the total solar eclipse, the moon obscures more and more of the sun’s light.

Totality

Time-lapse animation generated by SkySafari 6 Pro.

At the point of maximum coverage, during the total solar eclipse, the moon completely obscures the sun, blocking all its direct light.

Concluding partial phases

The concluding partial phases occur as the moon departs the sun and moves towards the left (eastwards).

History of the eclipse

Ancient times

For thousands of years, people have been fascinated with eclipses (total solar and total lunar), and observations were made all over the planet where advanced civilizations existed.

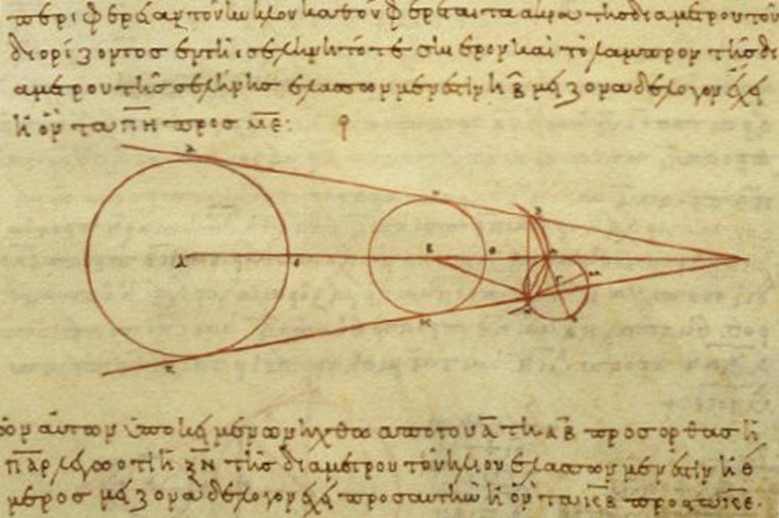

In ancient Greece, these observations were so important that they led a famous mathematician of the time—Aristarchus of Samos—to develop an estimate of the sizes and distances of the Earth, moon, and sun in terms of the Earth’s size, which, unfortunately, he did not know at that time.

While his numbers are a bit off due to his limited observing ability at that time, his reasoning was sound.

The end of the Great War and the rise of the superstar scientist

At the turn of the 1900s, a young German scientist revolutionized the world. The person was Albert Einstein.

Not enough can be said about Einstein’s brilliant mind and ability to turn our common ways of thinking on their heads.

Two of his biggest theories concern how objects appear to one another during extremely high velocities (the theory of Special relativity) and how the mass of a very large object, like the sun, can affect/distort space and time (the theory of General relativity).

In his 1915 paper on General Relativity, Einstein noted that the position of stars as seen next to the sun would measurably differ from the theory of Gravity that Sir Isaac Newton had predicted.

However, this was during the middle of World War I, and people were more engaged in survival than testing science.

Upon the war’s conclusion came a total solar eclipse visible in South America.

This would offer the world a chance to test Einstein’s theories in a precise scientific manner. Sir Arthur Eddington, a famous British scientist, went to the Príncipe (off the West coast of Africa) to observe the eclipse and try to detect this apparent shift predicted by Einstein.

Here was a distinguished British scientist working hard to prove the theory of a distinguished German scientist after World War I!

When he returned and reported his successful results, Einstein’s name became so popular that he became known worldwide – a scientist superstar!

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the solar eclipse

Ontario Parks greatly appreciates the assistance and guidance of Melanie Demers, former astronomy instructor at Six Nations Polytechnic.

It has long been known that a total solar eclipse was important in completing the confederacy of peace amongst five of the Haudenosaunee nations (Mohawk, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca—the Tuscarora nation was added to the confederacy later).

In Haudenosaunee oral history, the Hiawatha wampum is said to have been woven during a total eclipse of the sun, establishing peace among the nations.

Published papers also support that a celestial phenomenon (likely a total solar eclipse) coincided with the founding of the Haudenausonee Confederacy, marked by the creation of the Hiawatha wampum belt.

Research states, “During a ratification council held at Ganondagan, the sky darkened in a total, or near total, eclipse. The time of day was afternoon, as councils are held between noon and sunset. The time of year was either Second Hoeing (early July) or Green Corn (late August to early September.” (Fields, 1997)[1]

Other findings have further supported this research. In his online article Dating the Iroquois Confederacy by Bruce E. Johansen [2], the conclusion held by many researchers is that the confederacy started in and around 1142 AD as that eclipse would have been total in the area of the peace treaty and agrees with other archaeological evidence.

The Solar Eclipse became an important astronomical tool to mark this great event. It represented the founding of one of the oldest democracies [3] that has endured for centuries, upon which the world’s most powerful country based its own democracy. [4]

[1] Fields, A Sign in the Sky: Dating the League of the Huadenosaunee, 1997

[2] Johnson, Dating the Iroquois Confederacy, 1995

[3] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2018, Oct. 4). Iroquois Confederacy. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved June 1, 2021

[4] H. Con. Res. 331, October 21, 1988