Today’s post is by Jess Matthews, the chief park naturalist at Rondeau Provincial Park.

One hundred years ago, there was a lot we didn’t know about managing parks.

The idea of maintaining ecological integrity is relatively new. Ontario’s first parks were primarily established for recreation and tourism.

During the first half of the 20th century, wildlife was often seen as a tourist attraction or a nuisance. There was little understanding of how animal diseases spread, or how local populations were adapted to the places they lived.

Because park managers didn’t know about any of this, some animals found themselves packed up and shipped off far from their homes.

This is the story of squirrels from Rondeau Provincial Park that, due to their fashionable coats, traveled as far as the White House lawn.

Fashionable rodents

There was a time very near the beginning of Rondeau’s life as a provincial park where the black morph of the Eastern Grey Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) was a hot commodity for international trade.

The squirrels’ shiny black fur was highly regarded, and this resulted in many Rondeau squirrels being caught, shipped, and released into new ecosystems.

What’s more, in some cases, the squirrel trade was exactly that – Rondeau’s black version of the species being traded for the grey.

Although they are the same species, grey-coloured Eastern Grey Squirrels are more common in the southern part of their range. Black-coloured squirrels are more common in the north.

It could be that the grey morph squirrels that we see in the park today are the descendants of a trade that happened over 100 years ago.

Living lawn decorations

As early as 1906 there is correspondence between Isaac Gardiner, Rondeau’s first superintendent, and Frank Baker, the superintendent of the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C. The men arranged a squirrel swap, grey for black.

The animals were given no monetary value through customs, as it was seen as a direct exchange between the Canadian and U.S. governments: 16 squirrels for 16 squirrels.

Rondeau’s black morph squirrels were destined for the White House gardens and grounds, and were the beginnings of a short-lived boom in other groups taking an interest in the sleek dark coat of these bushy-tailed rodents.

Squirrels for sale

Over the following 30 years, requests were made of the park to supply feed stores, private businesses, and tourist destinations with black squirrels.

For the most part, these requests were filled for the lofty price of $5.00 for a pair, complete with express shipping to get the animals there alive. Considering inflation, this would amount to approximately $110.00 per pair today. The expense was put down to “the time and trouble of trapping, the crating, and the trip to town for shipment.”

According to historical correspondence, the appetite to move these squirrels was motivated by several factors. There was interest in providing the public with a product (the squirrels themselves), there was profit for the park, and there was an interest in reducing the number of black squirrels in Rondeau. They had become so abundant that they were becoming a nuisance.

Population explosion

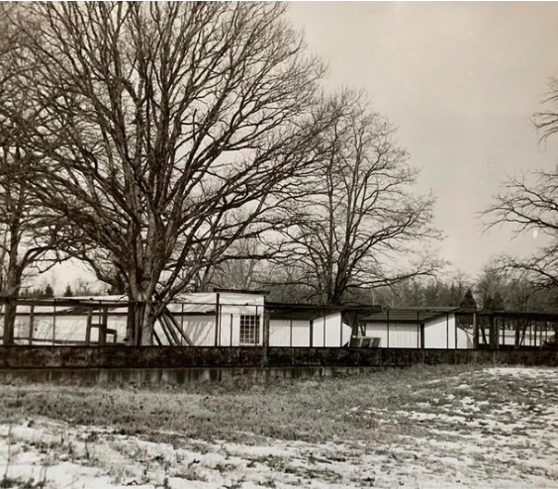

The major nuisance cited was the tendency of the squirrels to break into the feed house of the captive fowl in the park’s aviary. Subsidizing the squirrels’ diet with calorie-rich bird feed undoubtedly led to the explosion of their population.

By the 1930s, park staff seemed less inclined to live-trap the squirrels, due to some unfortunate squirrel deaths.

In 1931, the park superintendent noted, “On one occasion out of six, four died within 12 hours from nothing that we could ascertain, except possibly exhaustion or heart failure. The other two rubbed themselves so badly trying to get through the netting that they took all the hair off of their legs and heads.”

After this, there began a suggestion that this squirrel business was taking up too much time, and understaffing meant that priorities had to lie elsewhere.

A plague of squirrels?

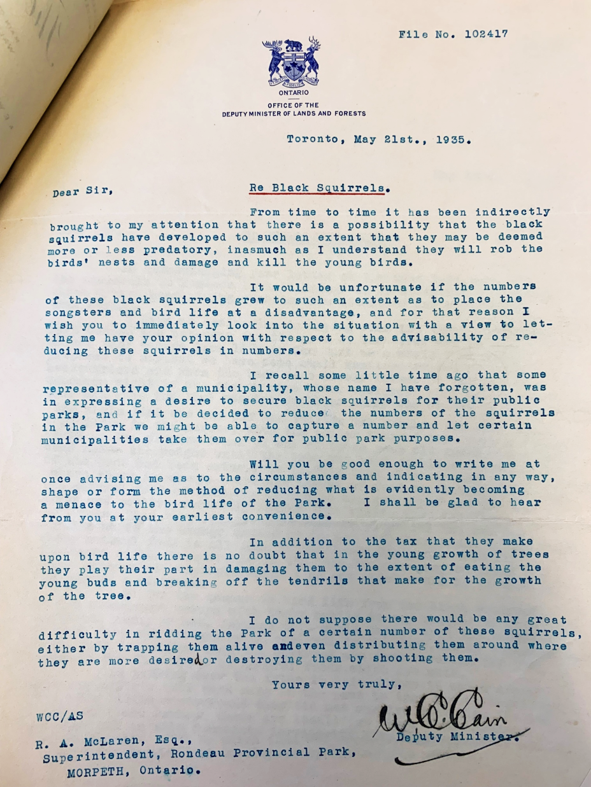

Unfortunately for the squirrels, many still believed the natural behaviours of the squirrel made them a nuisance in the park.

Squirrels naturally prey upon bird eggs and eat tree buds, which labelled them as pests. The unlucky rodents became wanted not only for their luster, but also for their removal from the park, usually by way of shooting!

It wasn’t until 1935 that the recently appointed superintendent Robert A. McLaren took a more ecological approach to the squirrel population. He noted that “squirrel life would appear to go in cycles, just as much of the wildlife does.”

At this time, and with this new outlook, squirrel harvesting and shooting was ended, except in the case that “nature does not thin out the numbers” by way of disease or other natural cycles.

Understanding ecological integrity

The path towards understanding the delicate balance within our parks has not been a straight line.

We continue to learn from every experience. This story is one of the reasons we have ongoing population counts of certain species in Rondeau, conduct bioblitzs, and monitor ecosystem health. You can help us monitor the wildlife in our parks by using the iNaturalist app.

All of this information helps us understand what Mr. McLaren was starting to see in 1935: that healthy ecosystems are all about the balance of native species, and provincial parks are here to help ensure that balance remains well into the future.

Today, Ontario Parks strives to maintain a high level of ecological integrity. This is the strength of each ecosystem based on the biodiversity, or variety of life, found within.

Part of this balance means controlling the spread of invasive and non-native species in each ecosystem, and ensuring that native species are not removed from the park’s boundaries.

We now understand and respect that Eastern Grey Squirrels play an important role in Rondeau and other parks. The history of Rondeau’s squirrels is a testament to how much we’ve learned over the decades.