Today, we join Discovery and Marketing Specialist Dave Sproule for a chat about the ecological and cultural significance of the beaver, which became Canada’s official symbol in 1975.

We all know beavers are industrious. They build dams, canals and sturdy homes called lodges, which are warm in winter. They repair all those dams and collect enough food to survive long northern winters.

We know beavers are well-suited to the Canadian environment. Beavers are amphibious – they’re more at home in the water than on land – with webbed hind feet, nostrils that can close, a third see-through eyelid that protects the eye when they’re underwater, and a big flat tail that acts as a rudder while swimming.

However, the biggest reason to celebrate the beaver is that it built Canada, shaping both its historical and ecological landscape.

~

Shaping history

There are two species of beaver in the world: the North American Beaver (Castor canadensis) and the Eurasian Beaver (Castor fibre). By the early 1600s, beavers in Europe were becoming scarce.

The waterproof fur that kept the beaver dry and warm while swimming underwater was also useful in making waterproof hats. In that era, there were no umbrellas, and waterproof clothes had to be waxed or oiled. As a result, waterproof hats made from the felt of the undercoat of beaver pelts were very popular.

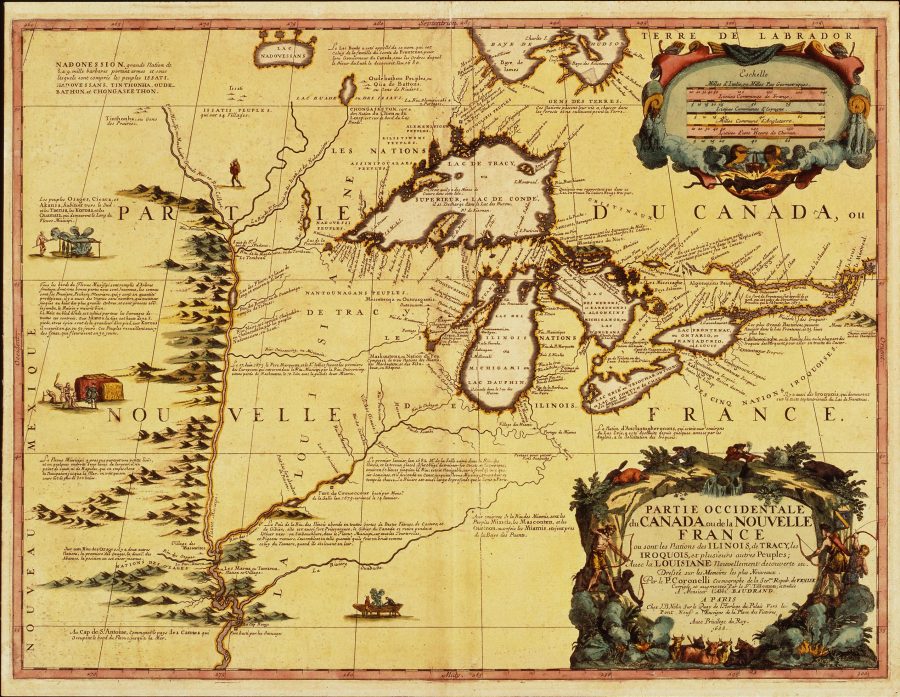

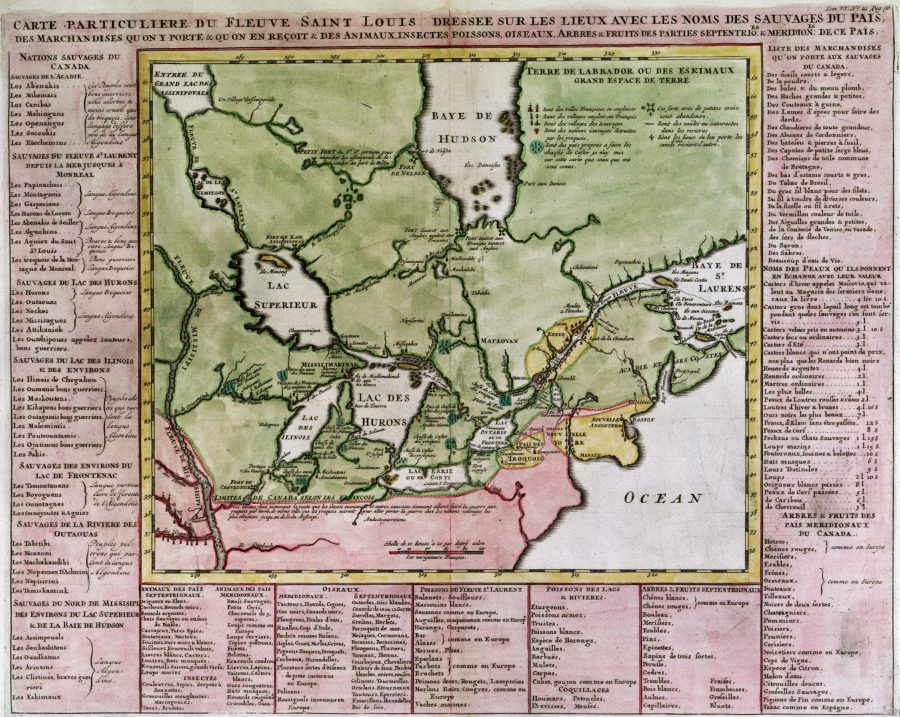

When French explorers learned that North America was home to plentiful beavers with thicker fur than those in Europe, they quickly set up trading posts and began a fur trade with the Indigenous peoples.

Trade quickly became extremely competitive. Wars erupted over hunting territory, first in the mid-1600s between the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and Wendat (Huron), known as the “Beaver Wars.” A few decades later, trade-fuelled war broke out between the French and the English on the waters of Hudson Bay.

And still, the demand for pelts kept growing. What was a practical item of clothing – a waterproof hat that kept your head and neck dry – also became a fashion accessory.

People needed to own several hats and wanted the latest style. Aristocrats, ladies, tradesmen, soldiers, and sailors all had their own styles.

By the height of the trade in the 1780s, two main fur companies faced each other: the Hudson’s Bay Company, established in 1670, and the upstart North West Company, which was run by a group of independent traders in Montréal. These “Canadians,” as the HBC men called them, set up a series of trade posts that crossed the continent, out-competing the older HBC.

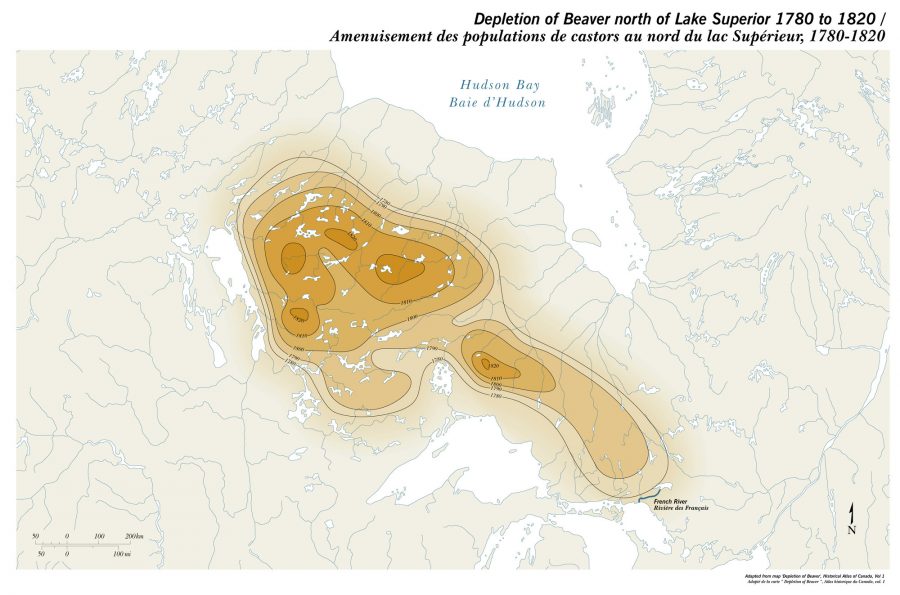

Trapping accelerated, and by the 1820s, the beaver had nearly disappeared from Ontario. The fur trade declined in the mid-1800s and felt hats began to be replaced by silk hats.

~

The fur trade built modern-day Canada

Economically, it was the most important industry for centuries; territorially, the trading posts established a Canadian presence as far as the Pacific Ocean, in direct competition with American fur traders and US territorial ambitions. Without the fur trade, Canada might not exist.

But the beaver paid the cost.

~

Shaping the ecological landscape

The fur trade removed beavers from much of their range across North America (it’s estimated that the beaver declined from about 400 million in the 1500s to near extinction by the 1850s).

The loss of beavers also meant a loss of biodiversity.

Biodiversity is the variety and variability of life on earth. The beaver is a “keystone” species for biodiversity – the changes it makes to the landscape in building dams, cutting down trees, and flooding valleys provide habitat for many other species.

By engineering its environment, the beaver changes the sameness of the forest into a variety of habitats. It opens up the forest canopy by cutting down trees and letting in the light; it creates more “edge” along ponds and wetlands, increasing shrubs and other plants which are habitat for insects, birds, and other wildlife.

Streams turned into ponds create more water for fish to swim in. Brook Trout thrive in deeper water, where springs feed the pond and keep things cool in summer.

Beaver ponds provide slow-moving water for aquatic insects and other invertebrates, frogs, turtles, muskrat, and mink.

As plant variety increases, waterfowl move in. Ponds are safe places to nest and raise chicks. For instance, the Black Duck depends on beaver ponds for 86% of its nesting habitat.

The loss of beaver in most of Ontario by the mid-1800s had a serious impact on biodiversity. Dams would have fallen into disrepair, eventually collapsing.

Ponds and wetlands would have emptied. Forests would have grown back into the openings beavers had cut, crowding into the dry ponds and wetlands, shading out the grasses, sedges, shrubs, and wildflowers, and decreasing plant, bird, and insect diversity.

Aquatic habitat would be reduced to small, shaded streams, eliminating the rich “edge” habitat along shorelines, as well as the warm shallows and cool depths.

Since the end of the fur trade, beavers have been recolonizing their old territory. Estimates of today’s population are between 6 and 12 million. They are again found throughout Ontario, and biodiversity has gradually followed.