Roger LaFontaine originally came to Algonquin Provincial Park looking for creepy creatures like leeches, snails, crayfish and rotifers in the early 2000s.

During that first season in the park, he became fascinated by the huge and strange marks seen all over Algonquin’s Highway 60 corridor left by a prehistoric worm. Since then, he’s devoted at least a day per year to documenting and studying some of Algonquin’s forgotten creatures.

Many visitors to Algonquin are in awe of the rocky shorelines and exposed rock outcrops throughout the park.

What only keen-eyed visitors may pick up on are the telltale marks left behind by a fantastic creature that sadly isn’t around anymore.

Findings from a lost journal

Back in the 1930s, strange marks appearing as vertical tunnels were seen in rocks along what would later become Highway 60.

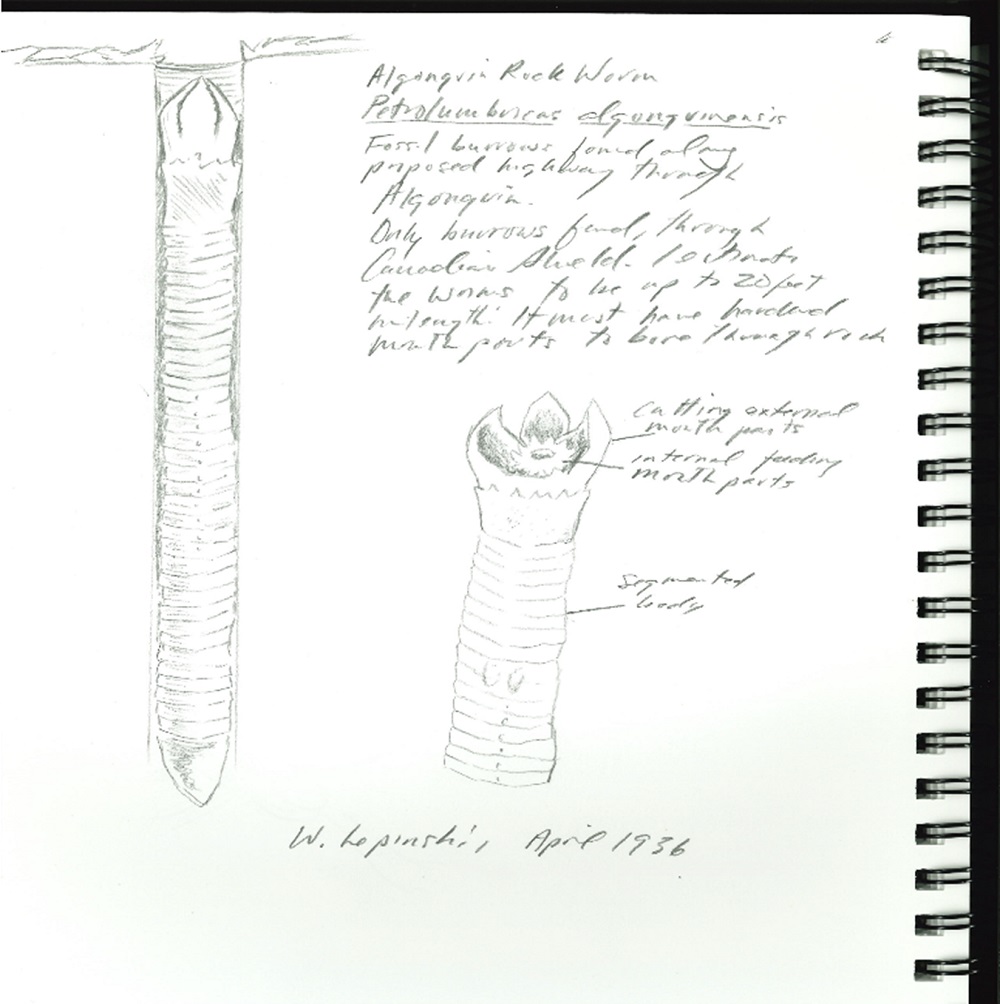

Naturalist Walter Lepinski working with the road crew would eventually go on to describe the creature that made these precise tunnels: the Algonquin Rock Worm (Petrolumbricus algonquinensis).

This was a species of large burrowing worm that specialized in boring tunnels through rock using hardened mouthparts.

Walter estimated that Algonquin Rock Worms were approximately 10 cm wide by 6 m long, featuring segmented bodies and head-ends covered with scales.

Lepinski’s observations were corroborated by strange notes and illustrations found in the journals of timber cruisers and timber chute operators before the turn of the century (pers comms, Norton Smithers, 2024).

Lepinski’s notes from this time are scant, but he did write in his journal

“Algonquin Rock Worm, Petrolumbricus algonquinensis.

“Fossil burrows found along proposed highway through Algonquin. Only burrows found through Canadian Shield. I estimate the worms to be up to 20 feet in length. It must have hardened mouthparts to bore through rock.”

Evidence of species past

Sadly, this species was one of the victims of the last Ice Age – the enormous glacier that covered much of North America in a crushing sheet of ice.

By the start of the last Ice Age 100,000 years ago, the rock worm would be wiped from the landscape.

In fact, following the melt of the glacier about 11,000 years ago, there would be no native earthworms at all in Ontario until they were introduced by humans just a few centuries ago.

Alas, no extant fossils exist of the Algonquin Rock Worm because animals with soft bodies rarely become fossilized. On top of that, that worm-killing glacier also scraped much of Ontario clean of its soil and softer rocks, including most fossil-bearing rocks.

Today, fossils of ancient animal life are found in limestone regions of southern and extreme northern Ontario.

To see these, check out parks like Presqu’ile Provincial Park, Craigleith Provincial Park, Kakabeka Falls Provincial Park – these parks host fossils that are hundreds of millions of years old!

As for the Algonquin Rock Worm, all we have left are the huge and mysterious burrows.

When the track or sign of an animal is fossilized, it is called a “trace fossil” or “ichnofossil.”

Modern effects of the Algonquin Rock Worm

While called the Algonquin Rock Worm in tribute to the place where it was first described, this species has since been found across much of eastern Canada and parts of the northern United States, with observations made all over the Canadian Shield.

Coincidentally, this lines up well with some of Ontario’s most iconic parks and drives, such as Frontenac Provincial Park, the eastern shore of Georgian Bay, Lake Superior Provincial Park, and more.

Today, we don’t have much to go on to piece together the life and ecology of the Algonquin Rock Worm.

The vertical burrows that we can see while travelling along the highway suggest they were good at orienting themselves to get to the surface and likely fed here.

Modern worms consume vast quantities of forest debris like dead leaves, and we assume that the Rock Worm did as well.

As modern worms feed, they leave behind poop, called worm castings.

One must imagine the immense heaps left behind by a 6 m worm and the nutrients spread onto the landscape, let alone the piles of pulverized stone at the burrow opening.

While we can’t know for certain, it is thought that Rock Worms were long-lived due to their size and the difficulty of boring through rock.

We have yet to find deep subterranean chambers attributed to the Rock Worm, and we suspect they are deep underground so unlikely to find them.

It is thought that the burrows provided homes for other species of long, narrow animals to use, from smaller worms and insect larvae to snakes and weasels.

In the past, as today, water trickles through these holes, perhaps entering the ground for long-term storage.

In winter, the water may freeze and thaw, and over millennia, this has cracked many rock outcrops, eventually creating mineral soil for plants to grow in.

Become a student of nature

You may be wondering, “So what? Why does this matter?”

We think the answer might come from Walter’s journal in 1936:

“Those building the road thought it was a waste of time to even ponder what made these burrows, and they teased me relentlessly for my curiosity in such matters. For the student of nature, everything is interesting and instructive to the eyes that can read it.”

If you happen to be visiting some of our stunning parks on the Canadian Shield this season, take some time to look for the burrows of the ancient Algonquin Rock Worm.

Photograph the tunnels from a safe distance, but don’t touch these sensitive fossils – researchers are still trying to glean what they can from them.