Sonje Bols is an interpreter and naturalist with Ontario Parks, and coordinates the Discovery Drop-in program at a number of parks in Northeastern Ontario. She loves dragonflies: watching them, catching and identifying their species, and pretty much everything else about them.

As soon as it’s warm enough to be outside in a t-shirt and shorts, chances are you’ll find me out “odeing.”

Odeing? Is that a typo?

The root of the word – ode – is the short form many naturalists use for Odonate, the scientific family name for a group of insects made up of dragonflies and damselflies.

To go “odeing” is to venture outside to catch and identify these insects.

~

Obsessed with odeing

Over the past few years, it has developed into a sort of obsession for me. A strange hobby, you may think, but hear me out.

I was first exposed to the world of odeing while working in the Discovery Program at Algonquin Provincial Park during the summer of 2009.

Specifically, I remember a casual conversation one afternoon between myself and two other park naturalists outside the staff house, where one stopped mid-sentence as he spotted a dragonfly zooming across the lawn.

He immediately grabbed his net, sprinted after the insect, and after a few wild swings, he finally managed to catch it. Pulling the wriggling insect out of his net, he sighed, “Ah, a Canada Darner. I thought maybe it was a Somatochlora.” (Somatochlora being a genus of rarely-encountered dragonflies, I later learned.)

I was amused and a little intrigued by this person’s intensity.

My first thoughts were: “Wait, there’s more than one kind of dragonfly?” and “Catching dragonflies is a thing?”

I soon learned that there are over 100 different odonate species in Algonquin alone (almost 200 in Ontario). And, yes, it is indeed a thing to catch them (there are over 64,000 Ontario odonate observations on the nature app iNaturalist and counting).

~

Learning from the best

That summer, I was lucky enough to accompany my coworkers on many odeing expeditions across the vast park. These were some of Ontario Parks’ talented naturalists, and they were always eager to share their knowledge with others.

Under their mentorship, I gained a lasting appreciation for these insects and a passion for catching and identifying them.

Unlike many other insects (butterflies and moths, for example) it’s relatively easy to handle dragonflies without damaging their wings, providing you are gentle.

They can be carefully removed from the net and held with their wings clasped together above their backs. This gives an opportunity for that all-important up-close look, for a relatively quick ID and release.

~

One-of-a-kind habits

Each species tends to have its own personality: the habitats they visit, their flight patterns, and the season in which they fly. And each is a treat to learn about.

I learned that the Fawn Darner can usually be found flying low over sluggish streams, and Stygian Shadowdragons and Vesper Bluets usually only come out at dusk.

Dragonhunters will hunt down and kill other dragonflies, and most odes will readily gobble up a deer fly if you dangle it in front of their jaws.

While I may have laughed at that zany dragonfly-chasing naturalist on the staff house lawn, by the end of the summer, I was just as crazy about odes.

~

So what is the big deal with catching odonates anyway?

To put it simply, it’s just fun. There’s nothing like the thrill of a successful swing of the net heralded by the sweet sound of a buzzing ode trapped in the fabric. I find it’s akin to catching a fish or scoring a goal.

Add in a few equally keen friends, plus some friendly competition (“let’s see who can catch the most species today!”) and the fun grows.

You can find dragonflies almost anywhere, and I find it particularly rewarding to explore new habitats to see what species I can find. No matter where I go, I can look forward to the possibility of catching a new one.

Equally rewarding is identifying them in-hand.

Birds and mammals sometimes only offer a quick glimpse and can be tricky to ID (juvenile warblers, anyone?), but odes are often strikingly patterned with distinctive features, making ID straightforward.

~

It’s also about the memories

My best odeing experiences (and some of my best memories) have always involved a good group of friends, an eventful foray into the wilderness, and the goal of catching an especially rare species.

I’ve stood in the middle of a thick swarm of Black-tipped Darners, catching six of them with one swing of the net.

I’ve trekked to countless bogs while being swarmed by black flies to catch a Delicate Emerald or Ebony Boghaunter.

I’ve spent the day canoeing and portaging in August heat to a secluded shoreline to find a Boreal Snaketail.

And it’s ALWAYS worth it — to explore a new landscape, get another ode on the life list, and live a great story to reminisce about. The challenges make the victory that much sweeter.

~

It’s no surprise you’ll find them here

All this net swinging isn’t just for fun — it also contributes to our knowledge of park wildlife and species distribution across the province. Ode-ers act like field scientists, monitoring population fluctuations and even finding previously unreported species!

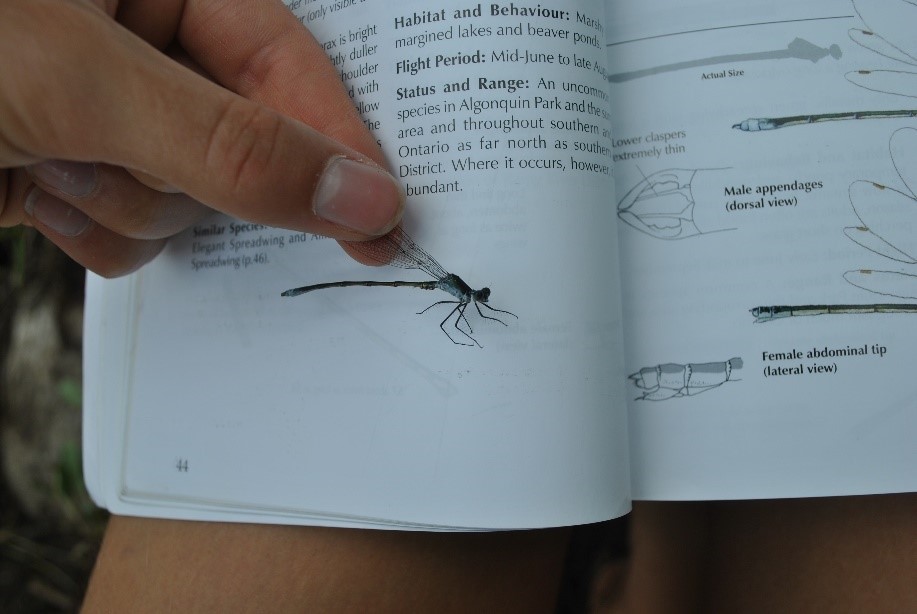

A few years ago, a group of former Algonquin park naturalists even published a field guide to the Odonates of Algonquin Provincial Park and surrounding areas. This is the field guide that kickstarted my understanding of ode ID and is regarded by many as the best for Eastern Canada.

I got my start odeing at Ontario Parks, and it makes sense — parks are havens for odonates. Parks protect vast stretches of wetland, which is a crucial habitat for their aquatic life stage.

Many parks also offer Discovery programs geared towards catching and identifying insects, as well as checklists of the species you may find.

However, if your curiosity about odonates is piqued at all, you don’t necessarily have to visit a park to start swinging a net!

I’ve caught good dragonflies everywhere, including city downtowns, corn fields, and suburbs.

There are numerous ways to enjoy the outdoors, make memories, and feel a sense of accomplishment, and odeing is just one of mine. I encourage you to grab a net and give it a try – you may just catch the “bug!”