This post was supplied by Discovery and Marketing Specialist Dave Sproule.

Fifty years ago, the huge freighter Edmund Fitzgerald was wrecked on Lake Superior.

This is the story.

~

Life on Lake Superior

As the saying goes, Lake Superior is a “weathermaker.” It is the resting place for many ships, boats, canoes, and their crews. Thousands of vessels have come to an untimely end on this inland sea.

Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake in the world by area, so big it creates its own weather, and affects the region’s climate.

Storms may appear at any time, but the combination of prevailing winds, weather, and seasonal changes means that the lake becomes more restless as the summer goes on.

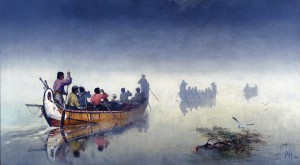

In the late 1700s, voyageurs with the North West Company paddled 10 m (36’) canoes laden with trade goods, as they headed west beyond the Great Lakes, and valuable furs when returning east to Montréal. On Lake Superior, they could expect to be wind-bound on shore one day out of three early in the season. By August they could be wind-bound two days out of three.

On Lake Superior, they could expect to be wind-bound on shore one day out of three early in the season. By August they could be wind-bound two days out of three.

By late autumn, the “Gales of November” have usually set in on Superior, creating hazardous conditions for even large modern ships.

~

The Edmund Fitzgerald

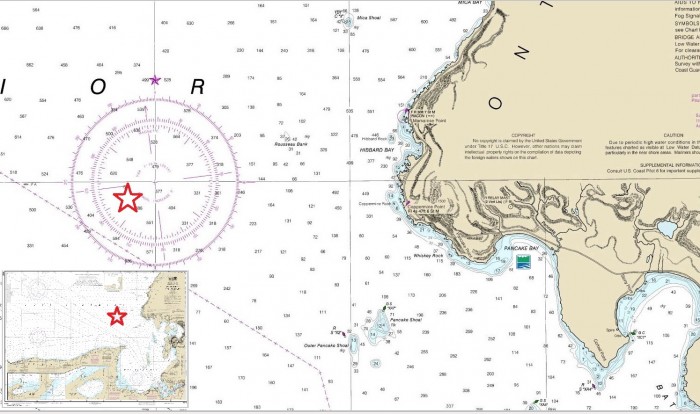

The most famous Lake Superior shipwreck is the Edmund Fitzgerald, a 222 metre iron ore carrier that sank 18 km off Coppermine Point, 60 km north of Sault Ste Marie, Ontario.

The Edmund Fitzgerald and its crew of 29 left Superior, Wisconsin on November 9, 1975 with 26,000 tons of iron ore pellets in its hold, bound for Detroit, Michigan. The ship was the largest freighter to sail the Great Lakes when it was launched in 1958.

The ship’s captain, Ernest McSorley, and fellow captain Bernie Cooper, of the Arthur M. Anderson, which was sailing with the Fitzgerald that November day, chose a route through the northern part of Lake Superior to avoid a storm that was developing to the southwest.

By the end of November 9, the storm had arrived, and fierce winds were whipping up waves of three to four metres high. But both captains had seen conditions like this before.

Conditions had worsened by the afternoon of the November 10, with snow and spray reducing visibility. The Fitzgerald was taking on water and both its pumps were going.

McSorley radioed Cooper that the Fitz was listing. The captain of the Anderson had noticed on his radar that the Fitzgerald had sailed very close to Six Fathom Shoal as the ship passed Caribou Island, as they steamed for the safety of Whitefish Bay at Superior’s east end.

By late afternoon, the Anderson’s captain was noting wind gusts up to 70 knots and waves up to 8 metres. At 6:55 pm, the Anderson was swallowed by a huge wave that ran from its stern to its bow, and another massive wave followed it.

By late afternoon, the Anderson’s captain was noting wind gusts up to 70 knots and waves up to 8 metres. At 6:55 pm, the Anderson was swallowed by a huge wave that ran from its stern to its bow, and another massive wave followed it.

Captain Cooper saw the two waves race south towards the Fitzgerald’s position 25 km ahead. Later, Cooper would say he was sure that these were the waves that had sank the Fitzgerald.

The last radio communication between the Fitzgerald and the Anderson was at 7:10 pm. The Fitzgerald was disappearing and reappearing on the Anderson’s radar – the height of the waves was causing interference.

Cooper asked Captain McSorley how they were doing. McSorley replied, “We are holding our own.” A few minutes later, the Fitzgerald disappeared from the radar screen for the last time.

~

Theories

Many theories have been posed on why and how the Fitzgerald sank.

The cause was “massive flooding of the cargo hold” which the US Coast Guard blamed at the time on loose cargo hatch covers.

Others dispute this, citing the ship’s passage over Six Fathom Shoal, which may have damaged the hull, as the reason the ship took on water, making it heavier and more susceptible to damage from the big waves the Anderson experienced.

It seems likely that the ship was overwhelmed by the waves and “submarined” bow-first below the surface of the lake. The weight of the ship drove it down into the lake bottom, 160 m below the surface.

When the Fitzgerald was found, it was discovered that it had split in two, almost right in the middle. An expedition to search the wreck and recover its bell revealed that the bow of the ship had received a significant impact.

Its cargo of iron ore pellets was spilled out over the lake bottom between the upright bow section, and the overturned stern section.

~

Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”

Only two weeks after the sinking of the Fitzgerald, Newsweek Magazine carried a story about the tragedy in its November 24, 1975 issue titled “Great Lakes: The Cruelest Month, James R. Gaines with Jon Lowell in Detroit.”

The story began: “According to a legend of the Chippewa tribe, the lake they once called Gitche Gumee ‘never gives up her dead.’”

This story inspired Gordon Lightfoot to write what he considered to be his most significant song, and certainly one that many Canadians and Americans know well. The song is a tribute to the men who sailed in the Fitzgerald and lost their lives on that stormy night.

~