Welcome to the Ontario Parks “Eyes on the Skies” series. This space (<– see what we did there?) will cover a wide range of astronomy topics with a focus on what can be seen from the pristine skies found in our provincial parks.

Heading outside? Here are our astronomical highlights for June, 2025:

~

The sun

One June 20 at 10:40 p.m., the Earth reaches the position of summer solstice, when we can enjoy the maximum amount of sunlight as the sun rises at 5:34 a.m. and sets at 9:20 p.m. (from central Ontario) giving us almost 15 hours and 46 minutes of light (see the March edition for more about solstices and equinoxes).

But, just like the winter solstice is NOT the day of the latest sunrise and earliest sunset, the summer solstice is not the day of the earliest sunrise and latest sunset. Those days are June 14 (when the sun rises at 5:34 a.m.) and June 27 (when the sun sets at 9:21 p.m.) from central Ontario.

In Canada, the summer solstice around June 21 is also National Indigenous Peoples’ Day, in recognition and celebration of the unique heritage, diverse cultures, and outstanding contributions of the Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

~

Sunrise and sunset times

The late sunsets in June provide people with the opportunity to enjoy spectacular sunsets.

| June 1 | June 15 | June 30 | |

| Sunrise | 5:38 a.m. | 5:35 a.m. | 5:38 a.m. |

| Midday | 1:24 p.m. | 1:26 p.m. | 1:29 p.m. |

| Sunset | 9:09 p.m. | 9:18 p.m. | 9:20 p.m. |

~

The moon

June’s lunar phases are as follows:

~

The planets

Jupiter and Mars are still quite visible in the western sky at sunset. Jupiter sets around 11:00 p.m. and Mars sets around 2:30 a.m.

In the morning sky, Venus and Saturn are visible in the east just half an hour or so before sunrise (you will need a good horizon and binoculars will help for Saturn).

~

Meteor showers

Meteor observing, especially in the dark skies of provincial parks, is one of the most enjoyable ways to get into astronomy.

You don’t need any special equipment other than your eyes!

A lounge chair, sleeping bag, and a friend are all welcome additions to enjoying the spectacle. If you take a look at our constellation charts, you can practice learning your constellations while you watch for the meteors.

A meteor shower occurs when the Earth enters the debris field of a comet that has long ago passed around the sun.

These bits of dust and grit, often no bigger than your thumbnail, enter the Earth’s atmosphere and burn up high above the ground (see our post on meteor showers for more information).

June is a relatively quiet month from a meteor shower perspective.

Nevertheless, observers are always able to see sporadic (random or unidentified shower) meteors as they may occur.

On any given night in the dark skies of provincial parks, you might see as many as five to 10 sporadic meteors per hour, especially after midnight.

~

Asteroid Defense Day

June 30 is the 117-year anniversary of the last major impact on the Earth.

Known the “Tunguska event”, a massive explosion felt (by seismographs) around the world occurred when a 100-metre space rock hit Siberia.

To make the public aware of the dangers from above, the United Nations has sanctioned this day for annual awareness of asteroid defence and their importance.

Click here to learn more about this Planetary Society event.

~

Featured constellations: heroes and serpents

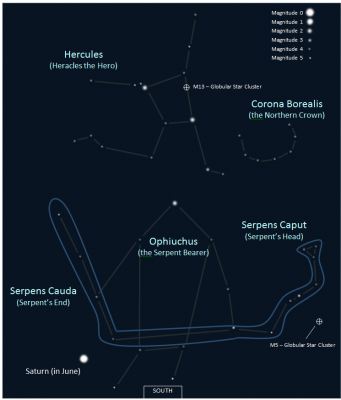

This month we will discuss the constellations of Hercules, Ophiuchus and Serpens.

This month we will discuss the constellations of Hercules, Ophiuchus and Serpens.

Ophiuchus and Serpens remind us of the ancient Greek legend for the origin of modern day medicine.

For all of his impressive tasks and great power, the constellation of Hercules is actually one of the smaller ones in the sky.

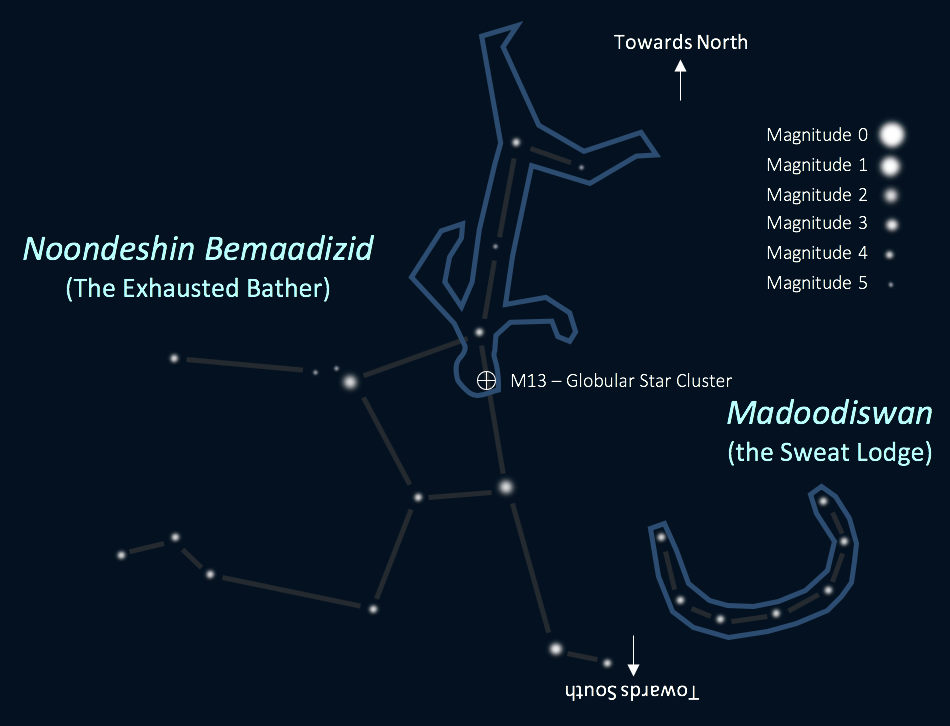

We also discuss the constellations Noondeshin Bemaadizid (the Exhausted Bather), which appears amid the stars of the Greek constellation of Hercules, and Madoodiswan (the Sweat Lodge), which appears amongst the same stars as the Greek constellation of Corona Borealis.

~