Welcome to the Ontario Parks “Eyes on the skies” series. This series covers a wide range of astronomy topics with a focus on what can be seen from the pristine skies found in our provincial parks.

Many people consider September to be the finest month of the year to enjoy Ontario’s outdoors.

The bugs have all but left and the daytime temperatures are cooler, making the weather ideal for strenuous activities such as hiking or canoeing. To top it off, the leaves begin their beautiful transition through the colours of fall.

With the much shorter days, the nighttime skies are full of celestial splendours that we hope you will enjoy discovering in this edition of “Eyes on the skies.”

Here are our astronomical highlights for September, 2024:

The sun

The sun continues its apparent drop in elevation and we reach and pass through the autumn equinox at 8:42 a.m. on September 22.

On this day, the sun appears directly above the Earth’s equator. Many people think that the amount of daylight and night is equal on this day. While the amounts are very close, the day in which we have equal day and night actually occurs a few days later on September 26.

Why?

The autumn equinox

The answer is an interesting one that most people are not aware of. It has to do with the way our atmosphere works as well as the way we mark sunrise and sunset.

First of all, our atmosphere bends light via a process known as refraction. That means when we see the sun appear at sunrise, it’s actually lower down, still beneath the horizon. Its just that the Earth’s atmosphere has bent its light to make it appear higher and, therefore, visible to us.

The same effect occurs at sunset when the sun has actually gone down under the horizon well before we see it disappear!

The second reason for the discrepancy between equinox date and equal day and night date has to do with the size of the sun.

We (logically) tell ourselves that sunrise occurs when we first see the sun and that sunset occurs when we can no longer see the last fleeting light from the sun.

However, astronomers measure the sun’s position not from its top edge (as seen at sunrise or sunset) but from its centre. Because the sun has some size to it, it takes an extra few minutes from the time that we see it at sunrise for the centre of the sun to clear the horizon.

And, of course, the opposite is true at sunset.

Due to both of these factors, we need a few more days in the autumn for the sun to rise later and set earlier for there to be equal day and night.

For those of us relying on daylight to paddle to that distant lakeside campsite or hike that last ridge before setting up for the evening, knowing when the sun sets is important.

Sunrise and sunset times

| September 1 | September 15 | September 30 | |

| Sunrise | 6:42 a.m. | 6:47 a.m. | 7:15 a.m. |

| Midday | 1:17 p.m. | 1:13 p.m. | 1:07 p.m. |

| Sunset | 7:52 p.m. | 7:27 p.m. | 6:59 p.m. |

The moon

The moon has long captivated observers of all ages. Even a pair of small binoculars will reveal the craters of the moon.

September’s lunar phases of the moon occur as follows:

The planets

Saturn is up all night long and is noted for its yellowish colour in the low southern skies.

Normally, the planet has distinctive rings, but as the planet travels around the Sun on its 30 year orbit, the orientation of the rings changes, and in some years almost become invisible.

This is one of those years. To the right is a recent image of Saturn taken by one of our Astronomers in Residence – Jo VandenDool – at the Killarney Provincial Park Observatory.

Jupiter and Mars rise a few hours after Saturn and Mercury makes an early morning appearance just before sunrise, best seen on September 9.

Comets, meteor showers, and satellites

Meteor observing, especially in the dark skies of our provincial parks, is one of the most enjoyable ways to get into astronomy.

You don’t need any special equipment other than your eyes!

A lounge chair, sleeping bag, and a friend are all welcome additions to enjoying the spectacle. If you take a look at our constellation charts, you can practice learning your constellations while you watch for the meteors.

A meteor shower occurs when the Earth enters the debris field of a comet that has long ago passed around the sun.

These bits of dust and grit, often no bigger than your thumbnail, enter the earth’s atmosphere and burn up high above the ground (see our blog on meteor showers for more information).

September is a relatively quiet month from a meteor shower perspective.

Nevertheless, observers are always able to see sporadic (random or unidentified shower) meteors as they may occur.

On any given night in the dark skies of provincial parks, you might see as many as five to 10 sporadic meteors per hour, especially after midnight.

In September, there are four meteor showers that produce only a few meteors each that contribute to these “sporadic” observations:

- Aurigids

- September epsilon Perseids

- Southern Taurids

- epsilon Geminids

Featured constellations

In August’s featured constellations, we discussed Sagittarius, Capricornus, and Delphinus.

There is a water theme in September’s edition.

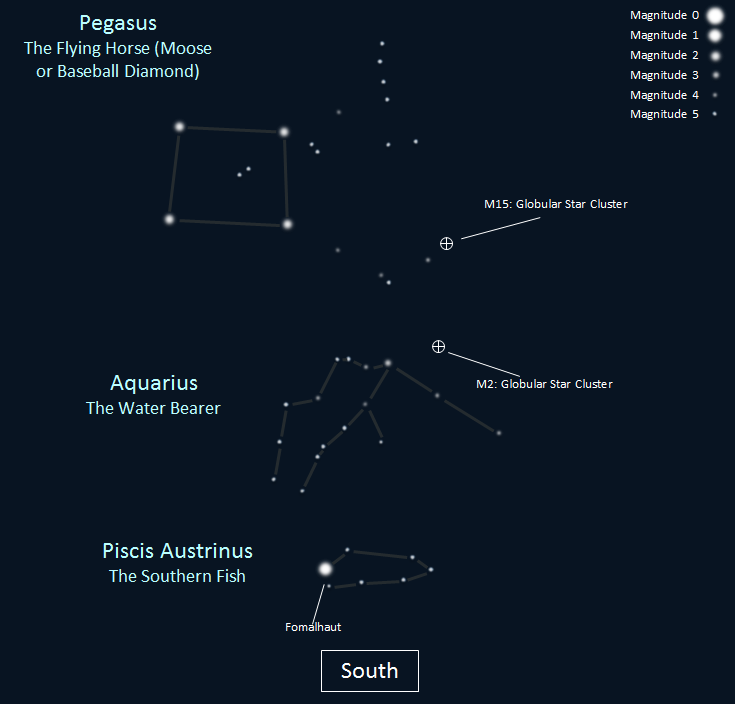

We discuss Pegasus the flying horse (moose or baseball diamond), Aquarius the water bearer, and Piscis Austrinus the southern fish.