Today’s post comes from former Operations and Development Program Intern Kayl Commanda.

My English name is Kayl Commanda. My Anishinaabemowin, or right name, is Opichi![]() .

.

I was named by an Elder in my community of Nipissing First Nation after the red chested spring bird, Robin, a symbol of spring and renewal.

This name has grown to mean a lot to me, and a lot of the teachings I have received about my name relate to the work I am doing as a firekeeper.

My favourite part about being in Ontario Parks is the consistent, guaranteed view and smell of smoke rising from campsites every morning and every evening, like clockwork.

Campfires are an imperative and integral element of any camping trip. Be it for cooking, entertainment, warmth, or just overall enjoyment, fire is undoubtedly a symbol of community.

~

Caring for a gift

In addition to the seven grandfather teachings given to the Anishinaabe, we were given four gifts to look after – Shkode, Nibi, Noodin, miinwaa Aki; fire, water, wind, and earth.

To be given the opportunity to care for these gifts is a gift in itself, and a gift that I was given several years ago.

I became an oshkaabewis – ceremonial helper – when I was 19 years old in my first year as an undergraduate student at Trent University.

During my five years as a firekeeper at Trent, I had the honor of learning from various teachers, both inside and outside of the classroom.

I spent time repairing a Wiigwaas Jiimaan – birchbark canoe, harvesting minoomin, firekeeping for sweat lodge, spending time on the land harvesting traditional medicines for my bundle, and learning my language.

I often woke to firekeep sunrise ceremonies and heard the singing of robins, giving even deeper significance to my name.

~

Anishinaabemowin firekeeping words

- Shkode – fire

- Ishkotens – match or lighter

- Shkode Asin – flint or Fire Rock

- Mishi / Mishenh – firewood

Long before my time as a firekeeper, I maintained a connection to fire by attending ceremony and spending my summers camping with my mom and brothers at Algonquin.

The time spent with family around the fire often left me captivated in the flames.

Lying in my parents’ laps long past my bedtime, I knew very early in my life that fire is an alluring presence to even the grownest of adults.

Fire, or Shkode in the Anishinaabemowin language, is symbolic of far more than warmth or a tool for survival.

Shkode is an avenue, a passageway to something far larger than ourselves.

Shkode evokes a sense of calm and warmth; feelings so strong and alluring to parents that even the youngest of children, without fail, conquer their nightly adversary: bedtime.

~

Fire is Medicine

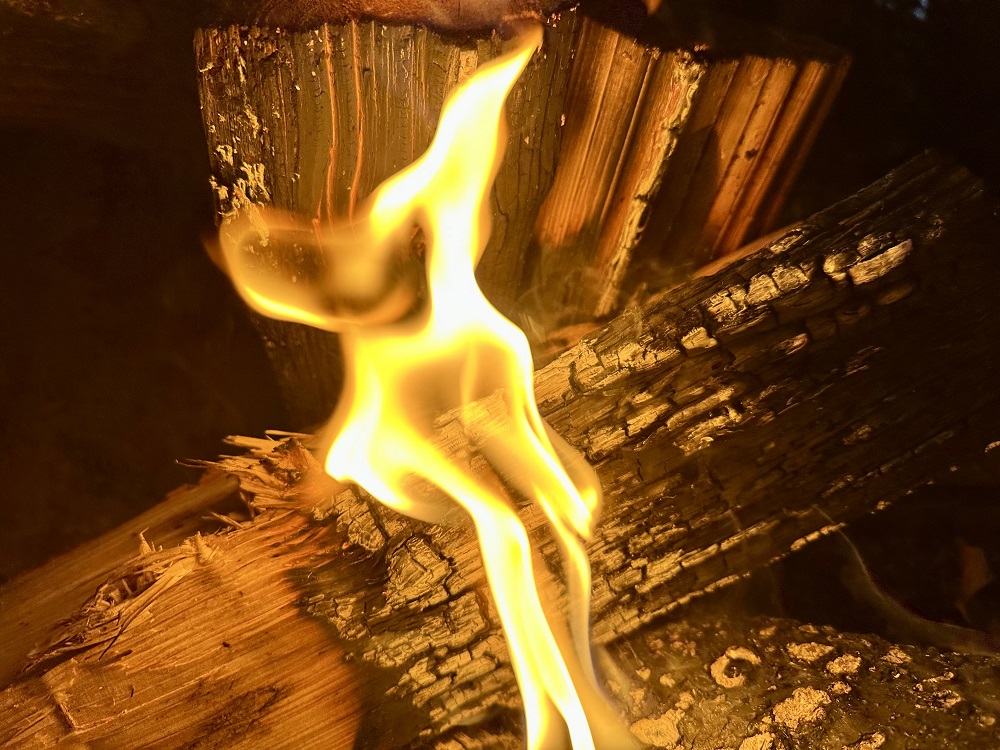

If you have looked into a fire long enough, and let your mind wander far enough, you have likely thought or spoke of Shkode’s resemblance to dancing.

Looking into a flame, be it as large as a bonfire or as small as a candle, is a practice of meditation.

I challenge your perception of Shkode’s movement and provide you with another: the steady rhythm of a beating heart.

Shkode, like many words in Anishinaabemowin, include the word Ode (heart) inside of it.

A fire beats like a heart.

When we gather around a fire, be it as a family on a camping trip or as a community for ceremony, a fire becomes a tool for unification and community building.

A 2011 study by Eindhoven University of Technology and Stanford University concluded that hearing someone’s heartbeat provided the same connection as looking someone in the eyes.

The heartbeat of our mother is the first thing that we hear – and its steady rhythm is something we subconsciously search for in the remainder of our lives.

~

What fire means to me

My grandmother, one of 13 children to my great grandmother, was only one year old when she was put into a French-speaking foster home in what came to be known as the Sixties Scoop.

My grandmother may not recall looking her mother in the eyes, but it is incontestable that she heard the steady, consistent rhythm of her heartbeat before she was even born.

What I said before about Shkode being an avenue to something larger than ourselves comes into play here.

As my grandmother, my mother, my brothers, cousins, uncles, and aunts watch the steady beating of an energetic flame, we are sitting together with our ancestors.

Shkode becomes symbolic of a bridge, allowing us to interact with family and community that no longer walk with us on Shkaakaamikwe, Mother Earth.

As a firekeeper, it is my responsibility to feed that flame. In a deeper sense however, it is my responsibility to ensure the avenue between my loved ones, both present and departed, remains open.

~

What does fire mean to you?

Not every fire has deep cultural significance. However, some of my fondest memories growing up were spent around a fire with my family in the very parks that I deliver cultural programming to this very day.

I was taught by a mentor that every family has a firekeeper, and that the title means something different to every family.

Nipissing First Nation has called my traditional territory home for time immemorial. It is an honour to walk in the same footsteps as my ancestors and be a firekeeper to my family, both in ceremony and on camping trips.

For me, being a firekeeper means holding space for the people I love. What does it mean for you?