This post was written by Dave Sproule, a marketing and Discovery program specialist with Ontario Parks.

If you are looking for a new trail to explore this summer, the Lonesome Bog Trail at Esker Lakes Provincial Park might be just the ticket! This 1.5 km interpretive trail sweeps around Sausage Lake and travels through a variety of habitats, introducing visitors to boreal forest ecosystems and ancient glacial landscapes.

The Lonesome Bog Trail begins on dry land, passing through a Jack Pine stand typical of the park’s boreal forest.

Jack Pine is a tree adapted to fire. Forest fires are a natural occurrence in the Boreal Forest, and Jack Pine actually need fire to reproduce. Their cones contain seeds that can stay in the cone for as long as 20 years before landing on soil and growing. To open though, most cones need a hot fire. The cones open after the fire and the seeds land on the burnt ground, clear of any competition and on the sandy or gravelly mineral soil they prefer.

Often Jack Pine are found in large stands and the trees are all of the same age, having sprouted after the same fire – many of Esker Lakes’ Jack Pine date back to a forest fire that burned here in the 1940s.

The trail skirts Sausage Lake, which is very scenic despite the name.

~

The Lonesome Bog

The trail leaves dry land for a boardwalk that crosses a spruce bog where some very crafty plants live. The bog is like a food desert with not many nutrients available for plants to live on. They must be able to survive with much less than the plants living in the forest, as they live on a mat of wet decomposing plant material.

This may seem like it should be nutritious for plants, but the bog is very acidic, and the food is locked up with little for plants to survive on. Somehow though, plants thrive in the bog, thanks to adaptations and strategies that help them in this difficult environment.

Most of the surface of the bog is blanketed in moss. The moss that grows in bogs, like many of the plants here, is also adapted to the wet, acidic conditions with low nutrient levels. Sphagnum Moss rules here.

~

Sphagnum is an interesting plant:

- it reproduces with spores, not seeds

- it has no roots

- it needs lots of water

- and plant eaters don’t eat it because it’s too acidic

~

The peat-maker

Sphagnum Moss also makes peat. As it grows, it develops into a thick mat. And Sphagnum Mosses have no roots, so the green (or red) part of the plant that captures sunlight also captures nutrients, mostly from rainwater.

The plants need to stay on top of the mat close to the light, growing on top of dead leaves and plant material that become the layers below. These layers accumulate over the years and the weight of the layers above compress them.

~

Labrador Tea is a flowering shrub that colonizes the bog

To save valuable resources, Labrador Tea keeps its leaves through the winter instead of dropping them. This helps the plant survive, as it doesn’t have to find the nutrients to grow new ones each year. To protect the leaves from dehydration in the cold winter months, each leaf has a waxy tough surface and a layer of brown “hairs” on its underside.

~

Black Spruce are the first trees to invade the bog

Black Spruce can tolerate wet, acidic conditions that many trees can’t. The trees can also clone themselves and move further into the bog by sprouting from branches resting on the bog mat.

They can make do with lower amounts of nutrients, but fungus helps the Black Spruce, as well as shrubs like Labrador Tea and other plants to deal with the lack of food. Fungi connect to the roots of the plants and help them pull in important nutrients like nitrogen.

~

Signs of historical human activity are hidden in the centre of the bog

Along the hike, the trail crosses a “corduroy road” where Jack Pine logs were once laid down to cross the bog in the 1940s to reach the Iris Gold Mine – the geology of the Kirkland Lake area is one of the richest gold-mining regions in the world.

Loggers also cut timber to shore up mine shafts, and the stumps can be found further along where the trail returns to dry land. The logs that make up the corduroy road are like islands that have been colonized by many of the bog plants, and are slowly but surely becoming part of the bog.

~

Carnivorous plants!

Some plants have developed an amazing strategy to get more food – they are carnivorous! Don’t worry though… they only eat insects! These plants are able to survive the acidic conditions of the bog by getting nutrients (especially nitrogen) from the insects they trap.

Pitcher Plants form a pitcher of water with some of their leaves. The pitcher has an enticing smell for insects, which land at the edge to get a better look.

Ultraviolet patterns also lead them to the edge, and once in the pitcher, downward-pointing hairs make sure they keep going. The leaf becomes slippery and into the water the insect goes. The “water” in the pitcher actually contains digestive enzymes which help the plant absorb the nutrients from the insect.

~

An ancient glacial landscape

A vast continental glacier covered most of Canada for thousands and thousands of years. When it began to melt from this area nearly 10,000 years ago, it left behind huge pieces of ice buried in sand and gravel washing off the glacier.

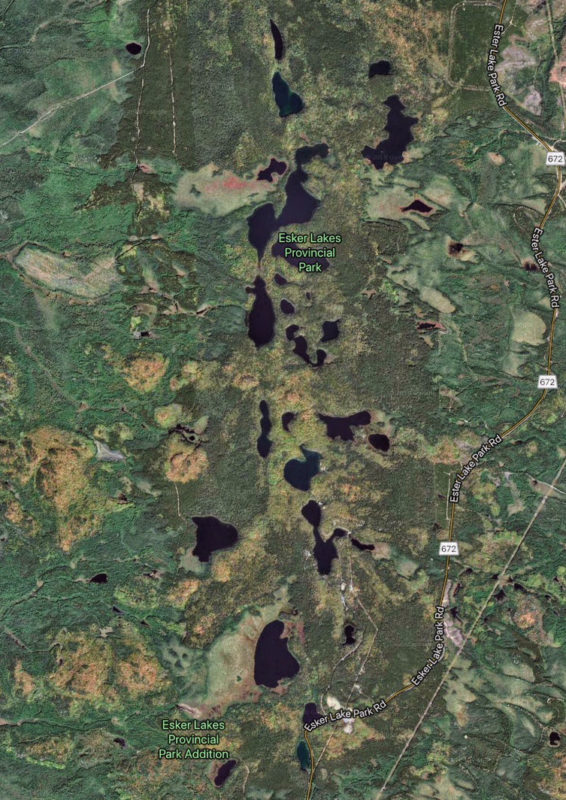

Esker Lakes sits on the bed of what was a wide glacial river flowing across the glacial ice – at over 250 km it is the longest esker in Ontario. The river helped to bury the blocks of glacial ice, which melted very slowly, keeping their shape.

The depressions, known as kettles filled with water from the melted ice, and are maintained by springs and groundwater. The lakes and wetlands left behind make Esker Lakes an amazing boreal forest lakeland.

~

Leaving the treed bog, the trail re-enters the forest

The Balsam Fir trees here have bumpy grey bark that is sticky with sap dripping in places. The bumps are blisters with sap inside. The sap can help the tree to defend itself against invaders like wood-chewing beetles – the beetle chews a hole in the bark and gets covered in the sticky goo. The sap later hardens and helps seal the wound in the tree.

~

Glaciers are dirty things

In the Balsam Fir stand sits a huge boulder. The boulder is more evidence of glaciation. Glaciers are dirty things. Only the newest snow on top is clean and white. The rest of the ice is filled with grit, and gravel and boulders that it picks up as it flows.

This boulder, known as an erratic, may have travelled from hundreds of kilometres north of here (or even further), frozen into the ice of the slowly moving glacier. When the glacier began to melt around 10,000 years ago, all of the sand, gravel and boulders were deposited onto the bedrock, leaving a hilly landscape that would later be colonized by the forest.

~

Esker Lakes is a quiet family-oriented park with a full-service campground with:

- Electrical campsites (65 of the park’s 103 campsites are electrical)

- Two comfort stations with hot showers, flush toilets and laundry facilities

- Two sand beaches and a dog beach

- Canoe and kayak rentals

Most of the park’s lakes are stocked with trout, and some lakes also have pike and perch. Bird watching is good at Esker Lakes, with many species of forest warblers being a highlight. Several other trails wind through the park’s forests, and portages link many of the park’s lakes, with two backcountry canoe-in sites on the route.

~