The deep green boreal forest of Kettle Lakes Provincial Park contains 22 beautiful little lakes. Of these lakes, 20 are actually called “kettle lakes” by geographers.

So what is a “kettle lake?”

To answer that question, we first must look at how kettles are formed.

~

An icy world

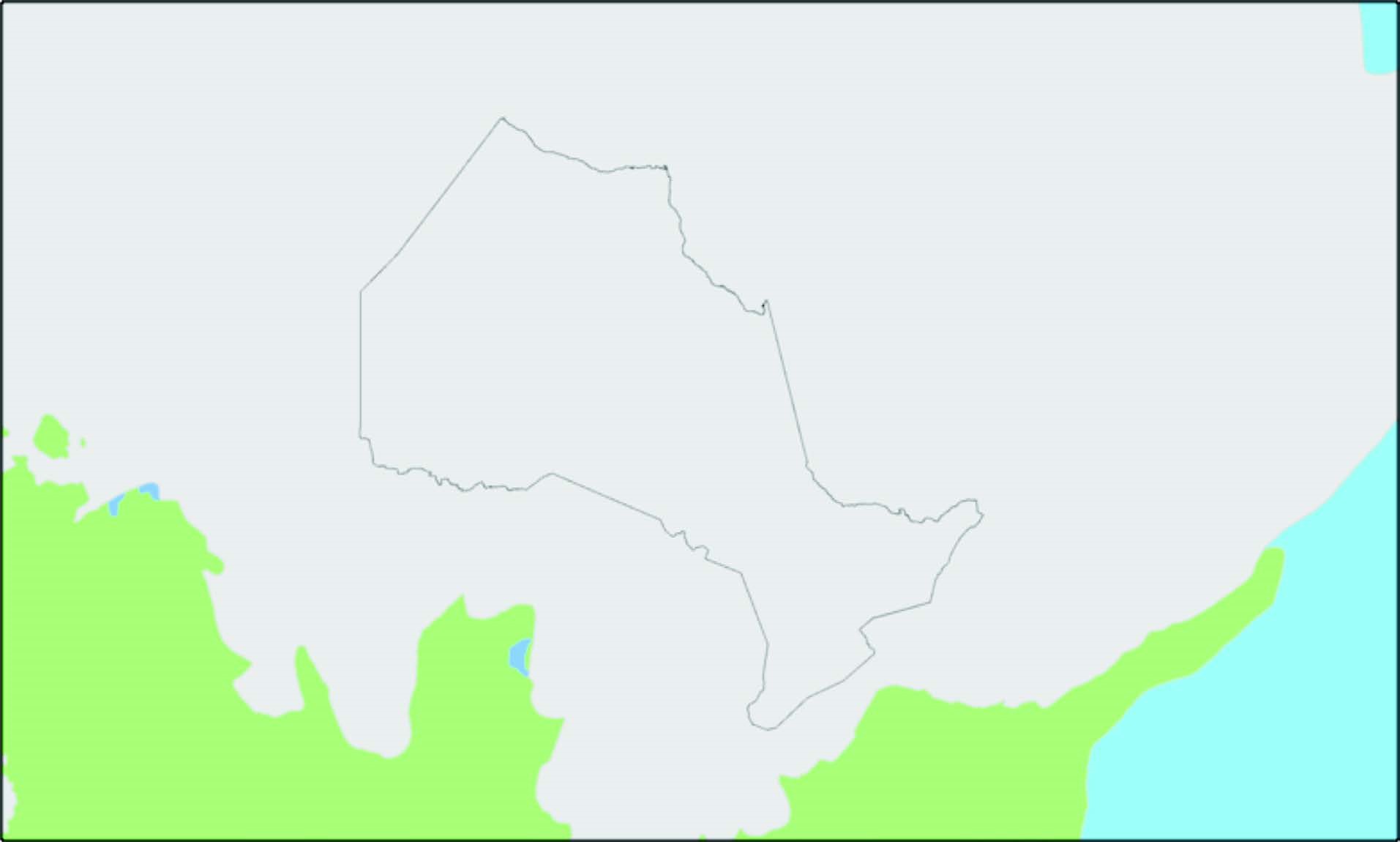

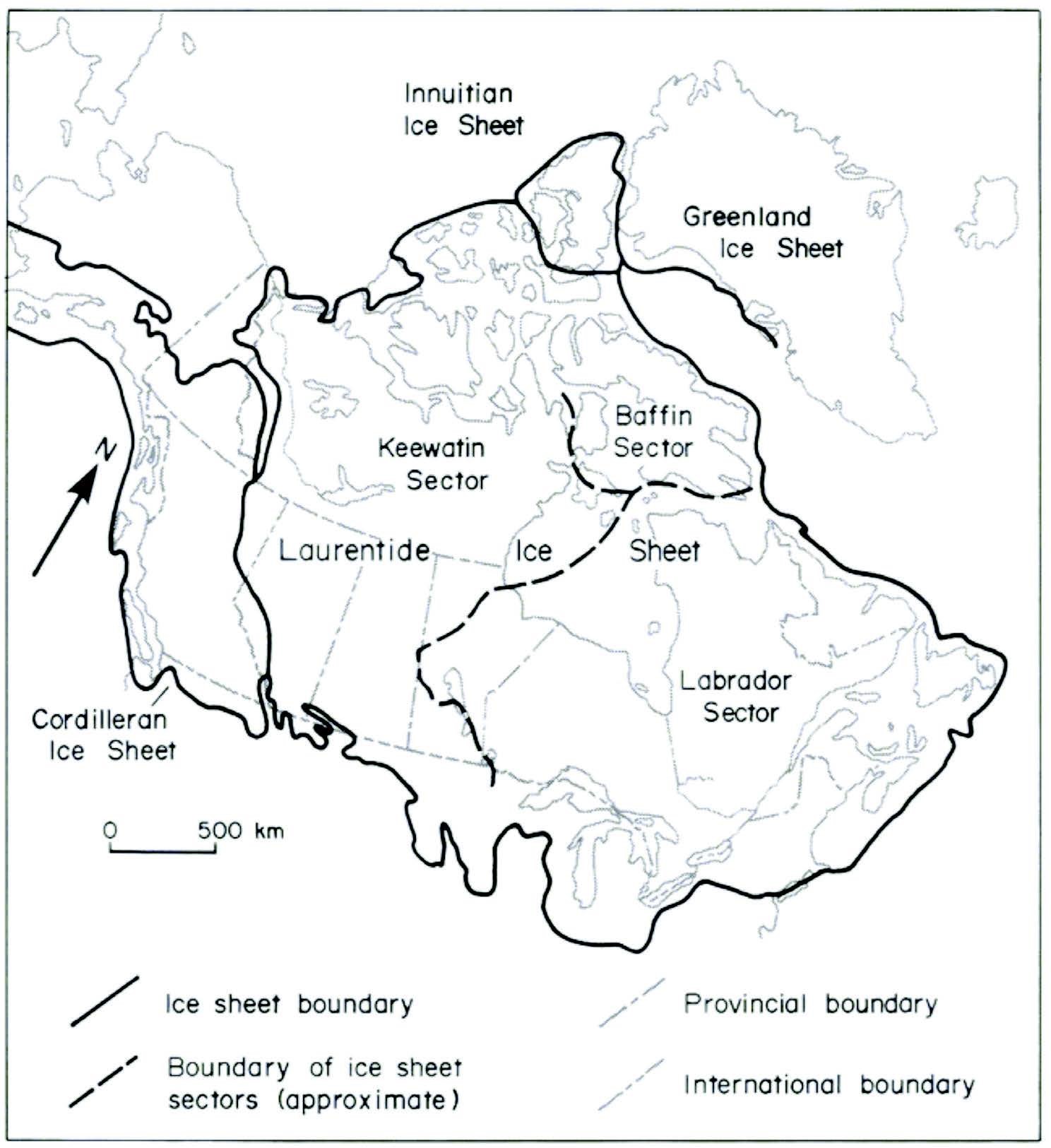

During the last glaciation of North America, ice sheets reached their southern limit, known as the “glacial maximum,” around 25,000 years ago.

This period is called the Wisconsin Glacial Episode, when the Laurentide Ice Sheet covered most of Canada and the northern United States.

Glaciers and glacial ice sheets grew and spread as snow accumulated and formed ice. The weight of that ice caused it to slowly spread out from the centre.

The centre of the Laurentide Ice Sheet is thought to have been northwestern Quebec, where the ice that formed grew and spread in all directions.

Imagine squeezing a bottle of ketchup onto a plate — as you squeeze more ketchup onto the plate, it slowly oozes out across the surface. When an ice sheet spreads like this, we say it “advances.”

~

Not so crystal clear

Glaciers are dirty things — literally. As the ice sheet advanced, sand, grit and gravel (and even boulders as big as houses) were picked up and frozen into the ice.

The ice sheet was like a conveyor belt — rocky debris it picked up slowly moved along to its edges as the ice advanced.

More and more of this rocky debris was picked up and frozen into the ice, making the ice like a huge sheet of sandpaper. As it advanced, it slowly ground down the earth’s surface and laid waste to mountain ranges.

In northeastern Ontario, mountains as high as the Rockies were worn flat by billions of years of erosion and glacial periods.

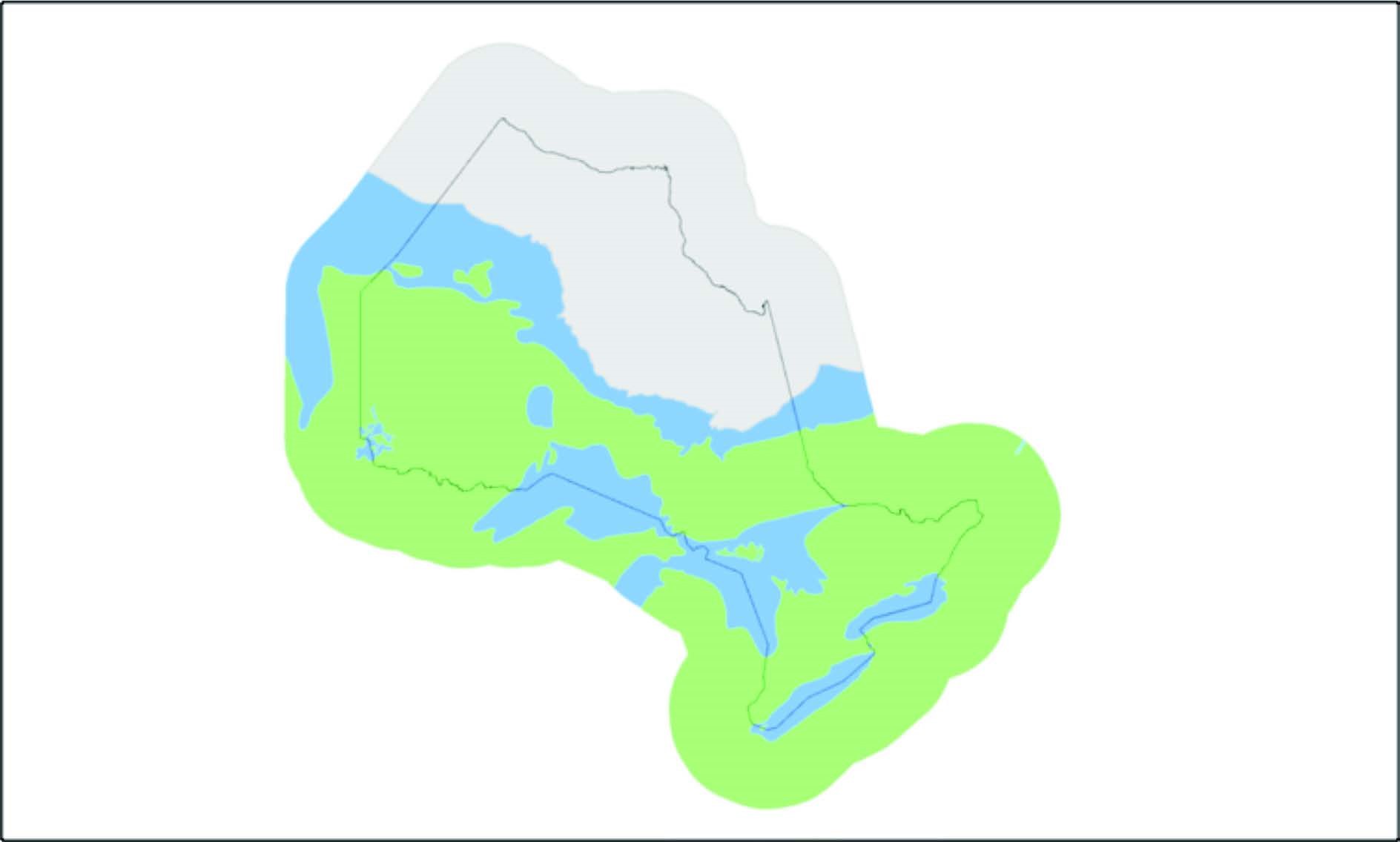

As the climate warmed, the southern edge of the ice sheet began to melt.

Eventually, the melting was greater than the advance of the ice sheet, and the glacier began to retreat from southern Ontario.

As the glacier retreated around the area that is now park, its southern edge melted and crumbled. Large ice chunks would break away from the face of the glacier and gradually be buried in the outwash plain (a vast flat plain created by huge amounts of meltwater from the retreating ice sheet).

After being buried, the ice chunks were covered in sediment from the glacial streams.

The area around Kettle Lakes Provincial Park is covered in a sandy delta laid down by a large river flowing off the ice sheet.

Formation of kettles

Since these huge chunks of ice were buried, they melted slowly, hidden from the sun and insulated from warmer temperatures that were melting the ice sheet itself.

If they had melted quickly, the deep, kettle-like depressions they left behind would have filled with more sediment and disappeared.

Gradually the meltwaters receded and the buried blocks of ice melted, slowly turning into depressions that filled with the melted ice water.

That ice water was replaced long ago in the park’s lakes by rainwater, melting snow, and groundwater flowing from springs.

In fact, all of the park’s 20 kettle lakes are fed by springs – none are connected to the surrounding watershed by streams because of the porous nature of the area’s landscape.

~

Favourable for flora and fauna

Some kettles are above the water table and are dry, or only have water in the spring.

Other kettles are small enough that a floating mat of plants can grow along the shore and gradually cover the surface to form a floating bog.

Kettle lakes are important habitats for all sorts of animals in the northern forest. Lakes are far less plentiful in the boreal forest that covers this part of northern Ontario, as the bedrock is often covered with a thick layer of glacial deposits.

Forest birds like the Yellow Warbler frequent the water’s edge and beavers sometimes build their lodges in them. Frogs, toads, and fish all live in and around kettle lakes. Trout are found in the park’s spring-fed lakes, which are cool and deep for their size.

~