Today’s post came from Cara Freitag, past Discovery staff at Neys Provincial Park.

There are many misconceptions about nature: climb a tree to escape bears, moose are friendly, coolers are strong enough to prevent bears from getting into your food.

Before I became a Discovery ranger, I thought that all insects were bugs, not just the Hemiptera order. My cousins in Germany thought that every Canadian had a pet Polar Bear!

None of these things are true.

Big mammals tend to get most of the attention, but there are misconceptions about smaller organisms too.

We have many visitors at the Neys Visitor Centre wondering: “Is that lichen killing those trees?” (Don’t worry, the answer is no.)

~

So what is lichen?

It’s not a plant, animal, or fungus. Lichen is outside of those categories.

It’s actually two organisms that live together – algae, an aquatic plant, and fungi, a plant-like organism that can’t photosynthesize.

Lichen can often be overlooked but once you learn to recognize them, hopefully you’ll notice many more.

If you’d asked me how many lichen species there are five years ago, I probably would have responded: “I don’t know, maybe 30?”, which would have been greatly underestimated as there are over 3,000 species in North America alone!

~

The first step

Lichen is a very important organism – they are the building blocks of ecosystems!

Even when you’re standing on what looks like bare rock, there’s a good chance that there are lichen underfoot.

It’s amazing how something so small can be so important!

~

Types of lichen

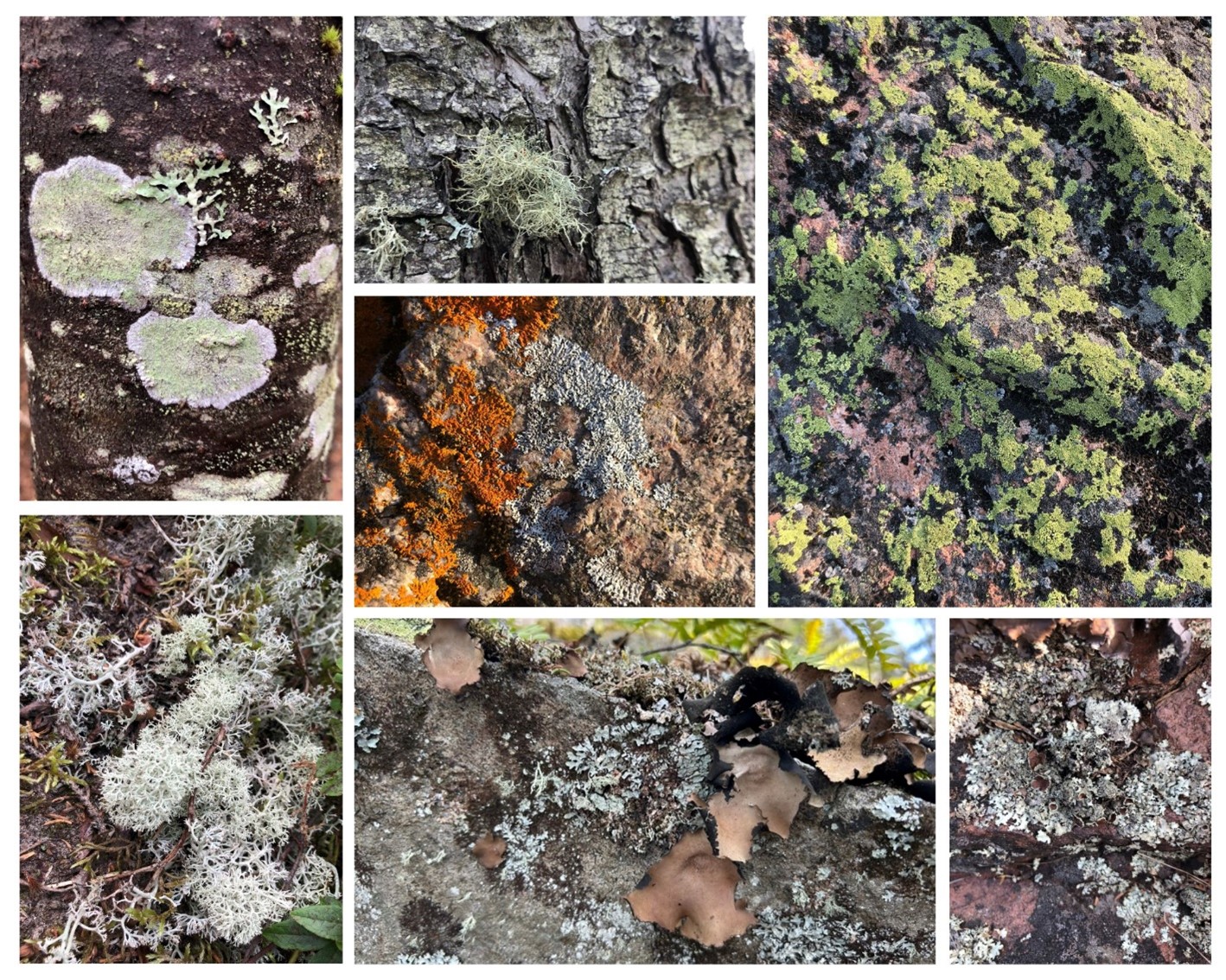

Lichen are categorized by their forms – what they look like.

There are:

- Crustose lichen (ex. Rhizocarpon spp.) that look like a crust that grows over rocks or tree bark

- Foliose lichen (ex. Parmelia spp.) that look like leaves or smooth bark and grow on rocks, trees, or soil

- Fruticose lichen (ex. Usnea spp.) that look like coral or string and grow on soil or trees.

It’s also possible to categorize lichens by where they live. There are rock lichen, soil lichen, and tree lichen.

~

Symbiotic relationships (the best roommates ever)

Organisms helping each other survive happens quite often in nature. Trees do it, birds do it, and fungi and algae do it!

These relationships are called symbiotic relationships. Two organisms enter into an agreement with each other and both organisms benefit.

People can enter into symbiotic relationships too! I’ve lived with a lot of roommates and at times we created a nice symbiosis where one of us would cook dinner and the other would clean up, or one of us would sweep the floor and the other would take out the garbage and recycling.

We worked together to make our house a nice, clean place to live.

With lichen, the fungi provide the structure (or the house) and the algae photosynthesize and provide the energy (or the food) that the fungi and algae need to survive.

Neither of them are able to survive without the other; bare rock is too dry for algae to live there by itself and fungi can’t get nutrients straight out of the rock.

This partnership allows them to fill an ecological niche that would otherwise be empty.

~

I’m lichen it!

Lichen are a great thing to have around. We’re lucky to find lots of lichen here at Neys. You can spot it on every trail, at campsites, and the day use areas.

They are an indicator species for air quality because they require clean air as free from pollution as possible.

An indicator species is a species where its presence (or absence) tells us something important about the ecosystem and environment. If there’s a lot of lichen around, the air quality is very pure. If there’s no lichen around, the air quality may be very poor.

The best place to find crustose lichen is on the Under the Volcano Trail, while fruticose lichen is best found on the Lookout Trail and Dune Trail. Foliose lichen can be found on the Point Trail.

In the city I live in when not working at Neys, I’d have to really search for lichen.

Sometimes I could find crustose lichen growing on trees or the sides of buildings, but they could be hard to find. Sadly, it likely means lower air quality there and I was missing those bright bursts of colour.

In contrast, in the spring when I returned to Neys, the lichens greeted me like old friends as they grew on the rocks, the trees, and the ground.

~

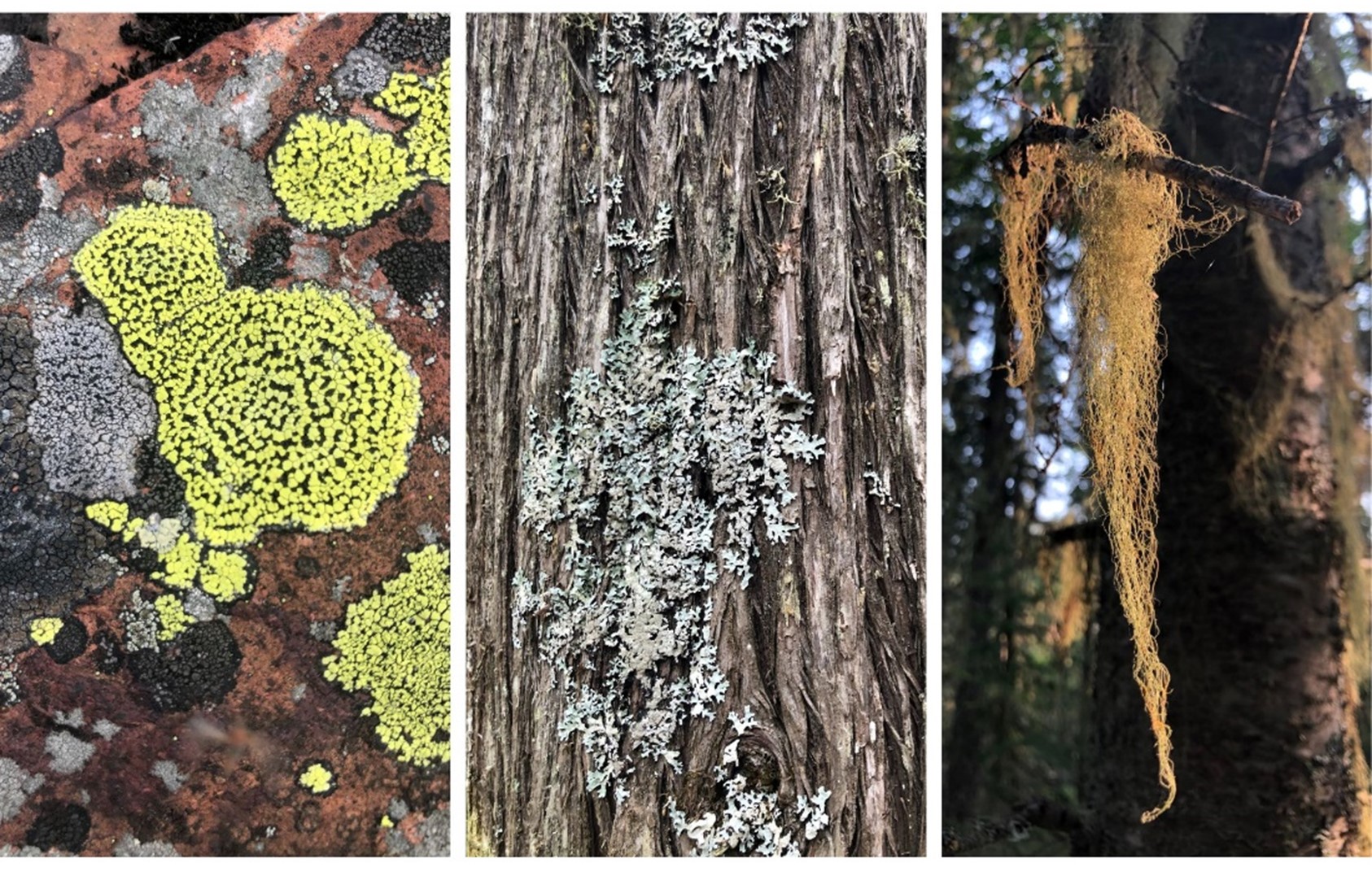

Old Man’s Beard

Old Man’s Beard is the common name for several species in the Usnea genus of lichen.

It’s a fruticose lichen that grows on the branches of trees here.

It takes a long time for it to grow the iconic, scraggly shape that gives the lichen its name.

It hangs from the branches of the pine trees and sways gently in the wind, lending an air of mystery to the forest.

When the fog rolls in (which it often does), the eeriness of the woods makes it seem as if the ghosts of Neys’ past could walk out from between the trees right in front of you.

In the 1960s, Scouts Canada planted Red Pines (Pinus resinosa) to reforest the park area. Red Pines generally don’t do well in the harsh winters on the north shore of Lake Superior.

However, they provide an important service to the forest even as they die and decay.

Their dead branches provide lots of habitat for Old Man’s Beard.

The people who come into the Neys Visitor Centre concerned about the lichen always ask us the same question: “is that lichen killing those trees?”.

The answer is, resoundingly, no. The lichen just found a nice place to live.

~

Seeking refuge

Ontario Parks offers a very important protected habitat for Old Man’s Beard.

There is less lichen biodiversity in cities. As Ontario (and Canada) becomes increasingly more urbanized, lichen are losing their habitat at an alarming rate.

Neys by itself protects 5,400 ha of natural environment from development.

Next time you’re outside, whether it’s at a provincial park, in a city, or on a farm, keep an eye out for our small friends the lichen.

Are there many of them? Or are they missing from your ecosystem?

Come visit Neys to see our lovely lichen!