Today’s post was written by Doug Gilmore, a recently retired superintendent of Woodland Caribou Provincial Park. The post commemorates the designation of Pimachiowin Aki as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

A journey can be defined as “the act of travelling from one place to another.” With every accomplishment there is often a journey, and the inscription of Pimachiowin Aki (Pi-MATCH-o-win Ah-KAY) as an UNESCO World Heritage Site was no exception.

Journeys also often include twists and turns and, most importantly, learning as you travel.

The beginning

The individuals who imagined Pimachiowin Aki began in separate places, united into a partnership, and ended at a common destination: inscription on UNESCO’s World Heritage Site List.

“The journey was a test of faith and patience, lots of hard work to prove our worth and achieving the final result, a sigh of relief and Pimachiowin Aki became a reality.”

— Ed Hudson, Pimachiowin Aki Board Member, Poplar River First Nation, (September 26, 2018)

It began in 2002, when five Indigenous Ojibway communities (Little Grand Rapids, Pauingassi, Bloodvein, Poplar River and Pikangikum) met to discuss shared interests.

As a result, they agreed to pursue the establishment of a linked network of protected areas in the boreal forest of northwest Ontario and eastern Manitoba.

Creating a partnership

Around the same time, government representatives from Ontario and Manitoba met to discuss the gap in representation of the boreal forest biome within the UNESCO World Heritage system.

They could possibly fill that gap with a trans-boundary proposal including Woodland Caribou Provincial Park in Ontario and Atikaki Provincial Park in Manitoba.

When the two groups learned of each other’s discussions, it became apparent that a partnership opportunity had great potential, and the journey began. As you can imagine, it wasn’t quite that easy. Lasting partnerships take time and hard work.

The first journey that began was the learning journey. The partners met, shared perspectives, learned about UNESCO World Heritage Sites and the process involved in inscription, but most of all, learned about and from each other.

Guided through the technical side of the process by Parks Canada, the new partnership explored the potential together and as separate groups. Finally, they committed to seek inscription in 2004.

Pimachiowin Aki (“the land that gives life”) was officially born.

“The land sustains us for more than just food, our spirits also. It’s hard to tell the outside world what it means to us.”

— Sophia Rabliauskas, Poplar River First Nation (December 16, 2004)

Gathering together

In the years between 2004, when Pimachiowin Aki was placed on Canada’s Tentative List of World Heritage Sites, and 2018, when the site was inscribed on the World Heritage List, the journey took the partners to all corners of the site.

They learned from Elders and community members about the cultural and natural significance of the area, but more importantly, what this area means to the people who live here and who look after the land. The partnership ebbed and flowed.

Although not all of the original partners continued with the group to final inscription, their knowledge and guidance informed the partnership and the project, and for that, Pimachiowin Aki will always be grateful.

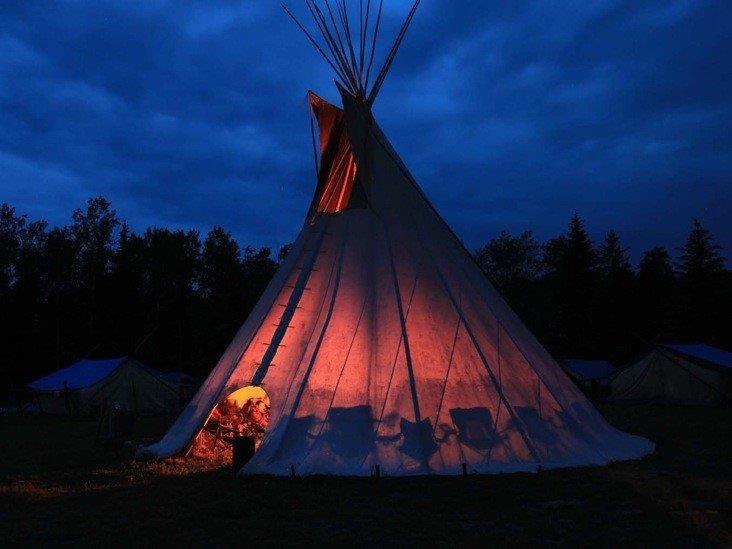

“The tipi represents the project. Under the branches we are all here together, that’s what makes us strong. Pimachiowin Aki is under the branches.”

— Augustine Keeper, Lands Coordinator and Pimachiowin Aki Board Member for Little Grand Rapids First Nation

Sacred sites

There is a shared belief among all of the Indigenous communities within the site that a strong link exists between the people and the land. This concept was critical to the initiative, and it cannot be understated that this concept, although foreign to those who are not raised in the culture, was going to be the foundation to the project and lead ultimately led to the success of the initiative.

Pimachiowin Aki provides an exceptional testimony to the continuing Anishinaabe cultural tradition of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan (Keeping the Land).

Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan guides relations between Anishinaabeg and the land; it is the framework through which the cultural landscape of Pimachiowin Aki is perceived, given meaning, used, and sustained across the generations.

Widely dispersed across the landscape are ancient and contemporary livelihood sites, sacred sites, and named places, most linked by waterways that are tangible reflections of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan.

On July 1, 2018, Pimachiowin Aki was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was inscribed as both a natural and cultural site, Canada’s first!

Keeping the land

It is described as an exceptional example of the cultural tradition of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan (Keeping the Land) that involves honouring the Creator’s gifts, observing respectful interactions with aki (the land and all its life), and maintaining harmonious relations with other people.

Pimachiowin Aki is the most complete and largest example of the North American boreal shield, including its characteristic biodiversity and ecological processes. Pimachiowin Aki contains an exceptional diversity of terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems and fully supports wildfire, nutrient flow, species movements, and predator-prey relationships, which are essential ecological processes in the boreal forest.

Why seek inscription, what can inscription do for the partners?

We’re glad you asked. It’s an opportunity to share a unique and beautiful landscape with all of humanity and to make the world aware of a place, a people and a link to the land that seems invisible to many.

With inscription comes recognition, and with recognition comes visitors. Conceptually, that’s not a bad thing, but it does take careful management to ensure that the features that convey the area’s outstanding universal value are not compromised, and that the Indigenous communities are able to take care of the land in the way that they always have.

The partners are proud of their individual communities, their traditional areas, and their regulated protected areas. They are keen to share them with the world for recreational and educational purposes.

The journey continues

Woodland Caribou Provincial Park is very proud to be part of Piamchiowin Aki, and will continue to work closely with their partners, as well as the Indigenous communities whose traditional areas are shared with the park, but who are not currently part of Pimachiowin Aki.

These cooperative relationships are important to Woodland Caribou Provincial Park and to the continued health of the park landscape.

“The UNESCO World Heritage designation brings recognition to this special place and the people that have shaped it. It truly is a gift to enjoy.”

— Superintendent Christine Hague, Woodland Caribou Provincial Park

Learn more about Pimachiowin Aki by visiting pimachiowinaki.org to keep up on the latest news and events in this unique landscape.