“The living edge.” It sounds more like a Bond film than a trail name, until you follow it through the woods.

The Living Edge Trail in Six Mile Lake Provincial Park is only a kilometre long, but it crosses such a variety of landscapes and habitats that it seems much longer.

It also spans time, giving visitors a close look at how the glaciers impacted the land thousands of years ago. Six Mile Lake Provincial Park is small on the outside, but big on the inside.

Six Mile Lake sits near the southern edge of both Muskoka and the Canadian Shield. The park contains that classic Shield landscape of pink granite, blue water and towering pines. Just two hours north of Toronto, Six Mile Lake is a little piece of northern Ontario.

~

Six Mile Lake sits at the southern edge of the Canadian Shield

The Canadian Shield is a vast expanse of ancient bedrock that forms the core of the North American continent. Most of it is over a billion years old, and some of it is much older. This is the “edge” in the Living Edge Trail…the southern edge of the Shield.

This hard bedrock is exposed in many places in the park. How did such old rock end up on the top? A billion years of erosion.

Mountains rise up, and wind, water and ice try to take them down. The last big event to grind away more of this hard rock was an ice age, which only ended about 14,000 years ago in this area, and had lasted about 20,000 years, which is a blink in geological time.

Still, it was enough time to grind down the Shield even more – as much as a few hundred metres of elevation — and when the ice was gone, there was a vast expanse of…nothing! No plants, no animals, no people.

Life had to start all over again, slowly moving north onto the barren landscape of sand, gravel, and open bedrock. That’s the “living” part of the Living Edge Trail.

~

Bedrock, forested areas, ponds and wetlands

The rock barrens are the open areas of bedrock found throughout the park, and are a hard place for plants to live, with little or no soil, little water and extremes in temperature in summer and winter.

Some of the bedrock surface seems much as it was all those millennia ago – the scratches left in the bedrock by stones that were frozen into the glacial ice are still visible in places.

~

Specially adapted plants

The Common Juniper is a prickly evergreen that grows from cracks in the bedrock, covering the ground to prevent other plants from competing with it for precious water. Some plants even hide inside of other living things to escape the extremes of the barrens.

Tiny algae find a haven within the walls of specialized fungus, and together they form lichen. Lichen can withstand extremes in temperature and moisture that many plants can’t. The fungi form the structures and store water, and the algae make the food. Together they produce substances, including a mild acid, which helps to break down the surface of the bedrock. In their own tiny way, they are helping with the slow process of making soil.

Pale Corydalis grows in the cracks, with a deep taproot that helps it find water in the dry bedrock. Its delicate pink and yellow-tipped flowers contrast with its toughness and ability to survive.

~

Skink central

The rock barrens seem empty in the heat of summer. However, you may be lucky enough to see Ontario’s only lizard speeding from one rocky crevice to another, hunting for insects. The Common Five-lined Skink is unfortunately not so common. It has a wide range across eastern North America, from northern Florida to northern Georgian Bay, but it is considered vulnerable and a species of special concern because of habitat loss, the pet trade, and roads.

Six Mile Lake is considered by biologists to be “skink central” because of the park’s healthy population.

One way for a skink to stay healthy is not to get eaten. If one is caught by its bright blue tail, the skink can shed it – that’s right, the tail breaks off and the lizard quickly escapes. The tail will grow back.

~

That’s one way of making soil

The slow process of chemically eroding the bedrock surface takes a while. Where the glacial ice left behind sand and gravel when it melted 14,000 years ago, plants found an easier place to grow.

This is called “mineral soil,” with little organic nutrients in it. Certain plants do better in it than others. The mighty Eastern White Pine, Ontario’s tallest tree and one of its oldest, does well in this mineral soil and seems to dominate the forest here.

After 14,000 years, some richer soil has developed at Six Mile Lake. Nearby Georgian Bay moderates the climate here and where that richer soil occurs, southern tree species make headway in moving north.

White Oak typically grows further south, and also seems more common in deep, moist soils with good drainage. Here though, it’s at the northern edge (there’s that “edge” again) of its range, and seems to do well in the park’s shallow soils. The White Oak’s sweet acorns are a favourite food of White-tailed Deer, Black Bears, chipmunks and squirrels.

~

The water had to go somewhere

The glacial ice didn’t just grind down the bedrock of the Canadian Shield; it scored it, and carved it, using the grit, sand and gravel frozen into it, like sandpaper.

This glacial activity left channels, grooves and hollows. These filled with meltwater, and later rainwater, to form lakes, ponds and streams. At first, they too had little in the way of nutrients, but nature is patient.

Living things began to live in them, making them richer in nutrients over thousands of years. Different kinds of wetlands developed, with different plants.

Along the trail, a long narrow pond shows a mixed personality. It has sections of open water like a typical pond. It also has floating plant mats more typical of a bog.

Sphagnum moss makes up these floating “islands” which are colonized by other plants like Cottongrass and Leatherleaf, that could not grow in the water themselves. Sometimes these floating plant mats cover an entire pond, beginning the process of turning it into a bog.

~

A toothy swimmer

Once forests began to grow around ponds and streams, a toothy swimmer moved in to help things along – the Beaver. Beavers are one of the few animals that engineer their environment.

They cut down trees, build dams, and sometimes even dig channels. They do this to travel safely through the forest. Wolves and other predators can make short work of slow-moving Beavers walking across the land, so they make waterways that safety take them to food and shelter.

The Living Edge Trail passes right by a dam that has been around for a while. It’s old enough that plants like Touch-me-nots have taken over the dam, making it more solid and more likely to last.

Beavers move into an area because it has an abundant supply of food. Beavers feed on branches, twigs and buds of trees. They especially enjoy poplar species such as Trembling Aspen, shrubby species like Speckled Alder, and even White Birch.

Beavers cut down the tall trees that are close to the water’s edge by chewing them with their sharp front teeth and then take the branches and store them underwater – like it’s their fridge. When these food sources become scarce, Beavers move on to other water bodies. After Beavers have left, their dams will eventually fall apart.

~

Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve (GBBR)

Six Mile Lake Provincial Park is not only on the edge of the Canadian Shield; it is on the southeastern edge of Georgian Bay. Eastern Georgian Bay is the largest freshwater archipelago (chain of islands) in the world.

In 2004, the area was designated as a world biosphere reserve by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The Biosphere Reserve designation recognizes the region’s outstanding natural and cultural features.

~

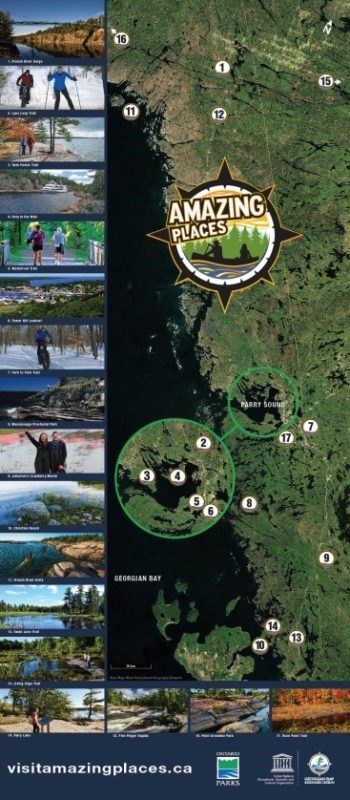

Amazing places of GBBR

In order to get people outside, the GBBR staff adopted the Amazing Places program developed by the Fundy Biosphere Reserve in New Brunswick.

In order to get people outside, the GBBR staff adopted the Amazing Places program developed by the Fundy Biosphere Reserve in New Brunswick.

Amazing Places promotes locations in the GBBR that are accessible to the public, and tell a story about the physical, biological and historical features of the reserve. These places present opportunities to explore, connect, and be inspired. They capture the range of natural and cultural values contained in the biosphere region. Seven Amazing Places in the GBBR are found within provincial parks.

The Living Edge Trail in Six Mile Lake Provincial Park is one of those places. Learn more about the GBBR and the other Amazing Places along Georgian Bay.

~

Visiting Six Mile Lake

Located on the shores of scenic Six Mile Lake, the park is only a couple of hours north of the GTA, and an hour north of Barrie, providing a great introduction to the north country if you haven’t visited before, or if you don’t have time for a long trip.

There are 200 car campsites, 53 of which have hydro. The park has a comfort station with hot showers, flush toilets and laundry facilities. There is a leash-free dog beach and two other sandy beaches. There are kayaks, canoes and paddle boats for rent.

The park store is well stocked with camper supplies and park souvenirs. Park staff lead the Park Ambassador program and Learn to Fish programs for beginners, as well as Discovery drop-in programs for families with kids.

Six Mile Lake is close to the great attractions in Huronia like Discovery Harbour, Ste. Marie Among-the-Huron historical park, and the S.S. Keewatin steamship.

Nearby is the Trent-Severn Waterway and the Big Chute Marine Railway at Lock 44.

~