Today’s post comes from Cara Freitag, senior park naturalist at Sleeping Giant Provincial Park.

Once upon a time, the North American continent tried to rip itself apart.

It’s easy to look at Sleeping Giant’s landscape and think that it has always looked the same, but every unique view gives us hints on how it has changed.

Now considered to be a geologically stable area, the rock formation known as the Sleeping Giant is a telltale sign of intense past geologic activity.

Would you believe me if I said…

The ground beneath our feet is constantly moving

The Earth isn’t fully solid and has a molten mantle under the surface. The ground that we stand on is called the Earth’s crust. It gets very complicated very fast when talking about what the crust is made of.

The crust, or thin surface of the Earth, can be broken down into two types: oceanic and continental.

Oceanic crust forms under the ocean and is denser and thinner than continental crust. Oceanic crust comes straight from the molten mantle and immediately gets cooled by the ocean. It is made of dark, heavy rocks like basalt.

Continental crust varies more, but is made of lighter, older rocks that cooled slowly over time. Continental crust is much thicker and less dense, so it sits higher on the mantle and rises above the oceans, giving us land to live on.

All of the Earth’s crust is broken up into pieces that form tectonic plates, like the North American plate that Ontario is part of.

The plates interact with each other and when they do, they can build mountains, expand islands and oceans, and cause earthquakes.

Why am I telling you this?

Because about 1 billion years ago, the area that would become Sleeping Giant Provincial Park was right on the edge of tectonic activity.

The rift that formed is called the mid-continent rift and it covered Lake Superior and extended down into the United States in a horseshoe shape.

One of the great mysteries of the world is why the rift stopped. We don’t know for sure. There are a couple of theories, but none have been proven.

It’s a hard thing to figure out since it happened so long ago.

But we’re sure that it happened?

We can tell where the rift was based on the type of rocks we see when the structure of the rift is exposed. Also, because the rock that formed in the rift is oceanic crust, which is denser than the surrounding continental crust.

The rock in the park that came from the rift is a type of rock called diabase. We see it all over the park: from the Sleeping Giant, to Thunder Mountain, to Tee Harbour, to the Sea Lion, and many other rocky outcrops.

Diabase is a dark, hard rock. It was formed underground and cooled more slowly, so its crystals are slightly larger than those of basalt. Otherwise, diabase and basalt have the same mineral composition.

Hang on, but what was happening during the rift?

Well, the ground was sinking, magma was rising, and the mantle of the Earth started intruding into the cracks of the soft, flaky sedimentary rocks that were in the area.

With immense pressure, the magma forced its way into the existing cracks and made them bigger.

These intrusions solidified and became known as sills (if they were horizontal) and dikes (if they were vertical).

But how can we see something that formed underground?

We can thank the Ice Age for that. Glacial movement causes a lot of change to landscapes.

Glaciers take up sediment, deposit sediment, scrape great gouges in the landscape, create lakes and rivers, move plants around, influence cultures and civilizations, and expose landforms.

The glaciers of the last Ice Age scraped away the softer sedimentary rock and left behind the stronger, now-exposed diabase structures in the park that we know and love today.

Formations keep changing

With about 10,000 years of exposure to the weather after the glaciers melted, the Sleeping Giant formation has changed since it originally emerged from the rock.

The park now has a lot of something called talus. Talus occurs when rocks erode, break off from their original landforms, and fall to the ground, creating a sloped area of loose rocks. Talus also refers to the rocks themselves and range in size from smaller pieces to larger boulders.

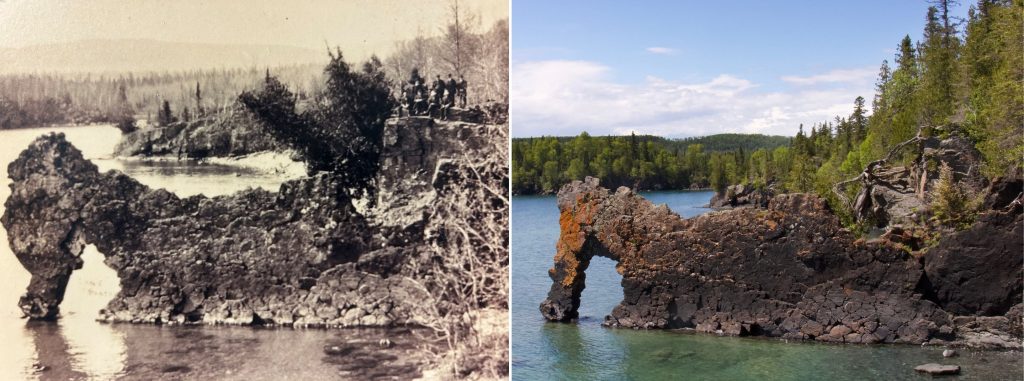

The park’s Sea Lion rock formation has also experienced a lot of change.

After emerging from the ice, the rock formation was slammed by Lake Superior’s waves and rocks (which were picked up by the waves) for about 10,000 years. It was also affected by the harsh temperatures of Superior, which changed what the diabase dike looked like through a process called freeze-thaw erosion, which weakens the rock.

From looking like a flat sheet of rock, to a lion sitting and looking out into Lake Superior, to a rock arch that sort of looks like an elephant, to the future where it may be a rock tower in the lake once the arch eventually collapses, the Sea Lion formation is in a constant state of change.

While visitors to the park have seen very similar landscapes for the past 100 years, erosion is constantly happening.

Every year, more rocks fall from the cliffs of the Giant, more waves slam into the shoreline and rock arch, and the wind and rain whisk away soil from the cliffs.

Every day the landscape is a little bit different, although often unnoticeable, and over decades we may be able to see the changes taking place around us.

Change is a natural process. And we cannot stop it.

Someday, the Sea Lion will crash into the waves of Lake Superior and cease to exist. We can’t prevent this from happening, and that’s not a bad thing.

The beauty of the park will still exist; it will just be different.

Visit Sleeping Giant Provincial Park to see the evidence of the rift for yourself!