Salamanders are iconic and influential members of northern forest communities. As one of the most abundant vertebrates in eastern North American forests, salamanders are considered “keystone species” because of their disproportionate roles as predators and prey in regulating food webs, nutrient cycling, and contributing to ecosystem resilience-resistance.

In addition to fulfilling key ecological functions, amphibians are our modern-day “canaries in the coal mine,” serving as a measure of environmental health.

Studying salamanders

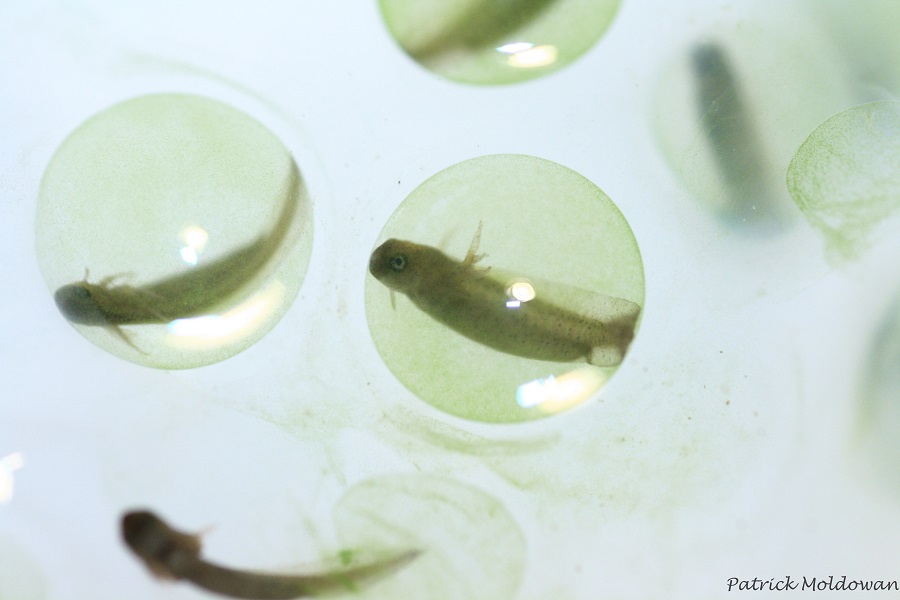

The Bat Lake Inventory of Spotted Salamanders (BLISS) research project in Algonquin Provincial Park is celebrating 13 years in 2021!

This study collects baseline data on salamander populations to better understand what a healthy population looks like and the role of these animals in the grander environment.

Patrick Moldowan (PhD student) and his supervisor Njal Rollinson at the University of Toronto coordinate the BLISS project*. Glenn Tattersall, a professor at Brock University, officially began BLISS in 2008 and has been instrumental in supporting students throughout the salamander study.

This story from the point-of-view of a male Spotted Salamander takes place during spring migration and breeding. It was written by Patrick Moldowan and inspired by long-term BLISS supporter, David LeGros (who is not an amourous salamander).

The story

When people think of great migrations what often comes to mind? The journey of wildebeest across the Serengeti or the oceanic transit of neotropical birds, perhaps?

Salamanders — so unassuming — are easily overlooked.

The journey begins

Now imagine: you’re 10 cm long, have short and stout limbs, and crawl on your belly. Your skin is wet, sticky and porous. For the past six months, you have called a rotted tree root hollow or maybe an abandoned rodent burrow a comfortable overwinter retreat.

Safe below the frost line and in pitch-black darkness it is not food that you have on your mind, but rather a mate. Somewhere in the freshly thawed forest there is an alluring pond. You must travel almost a kilometre through the prickly spruce underbrush, the next generation depends on it.

Finally, the subzero days are no longer, but the frigid nights still persist. Timing is everything. Too early and you risk freezing. Too late and you have missed your opportunity.

At first rain, you will move.

Over mountainous patches of snow, among luxurious mossy beds and under the downed trunk of a once towering pine, toppled during the last winter storm of the season.

You are not the only one on the move.

Your smaller brethren, a Red-backed Salamander (Plethodon cinereus), is at the soil surface too. There will probably be a large turnout this spring. The fall rains provided great feeding opportunities and you have plenty of fat reserves remaining after winter.

How long will the journey take? Four nights, maybe five. You are lucky to be one of the few beasts braving the cold.

Although you must not be too complacent; predators are in hiding. That poison sequestered in your skin can only get you so far. Any predator foolhardy enough to take a bite will get an oozing dose of the concoction, but still some have figured their way around it.

Onward

As you continue to approach the pond the chorus is deafening. Ah, the Spring Peepers (Pseudacris crucifer) and Wood Frogs (Lithobates sylvaticus) made good time, with their long legs and all. The call of frogs across the landscape seems extra conspicuous given the dead of winter that immediately preceded their reanimation. Overzealous, they are . . .

It’s getting late and the moon is climbing high. The first plunge into Bat Lake always feels like a shock to the system.

It might just be the cold, or perhaps the promise of another year ahead. It feels like home. While the days of gills are long past as you recount on the summer you spent hidden amongst the mud, dropped Leatherleaf and Labrador Tea leaves and thick shoreline moss.

You were yet to earn your spots in the wide world that lay beyond the water’s edge. The slick-shelled swimmers (predaceous diving beetles), trap jaw monsters (dragonfly larvae), and lightning fast jabbers (Giant Water Bugs) were always something to be wary of. These dangers have not entirely passed.

There is little time to waste. It may only be a night before mates arrive, all weather pending. And so you settle in.

A submerged mossy hummock gently sloping down from the shoreline: this is it. A broken Leatherleaf stem is just the centerpiece for the occasion.

You dread this part. You have never prided yourself as a landscaper, but you set to work nonetheless. There is no use wasting time now. Ah, this patch of moss will do, and that submerged snag. Piece-by-piece, your perfectly manicured sperm garden comes together, not a spermatophore out of place.

You finish with not a moment to spare. From the shallows you spy a pair of beady eyes staring back at you.

Slipping ever-so-gracefully into the water a female appears and begins to investigate your efforts. She is taking her time, a good sign.

She circles. Is she playing coy? All right chap, it is time to impress. Some nuzzling, a tail wag and straddling ensues in an effort to further interest the female. It has been a long winter. Are you sure that you still have it?

Round and round the garden, she is keeping you guessing. It turns into a game of follow-the-leader as you take the front and guide her to the middle of the garden as she gingerly walks over a few spermatophores before freezing in place. She crouches. Ever so slowly she aligns and gently taps the base of her tail against the gelatinous capsule.

With little hesitation, the spermatophore disappears into her reproductive tract. The female takes a few steps forward and picks up another. A sigh of relief, you’ve still got it. The female doubles back around and returns your nudges. As she turns tail and heads toward the thick leaf-litter bed you follow. It has been a long overland trek for her tonight; she will lay her eggs tomorrow.

In a flash of spots, you both disappear in synchrony.

The early spring wake-up paid its dividends.

*The BLISS project would like to thank our many student volunteers, the non-profit Algonquin Wildlife Research Station (follow along for frequent updates on their wildlife research on their Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter pages), and the support of Ontario Parks. Donations for salamander studies, among many other Algonquin wildlife research and conservation projects, can be made by contacting the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station or visiting their Patreon.