Today’s post comes from Evan McCaul, Ecologist with Ontario Parks’ Northwest Zone.

While conducting an ecological inventory of Brightsand River Provincial Park, Ontario Parks staff witnessed and recorded a large scale emergence of dragonflies, including a Dragonhunter, the largest clubtail dragonfly in North America!

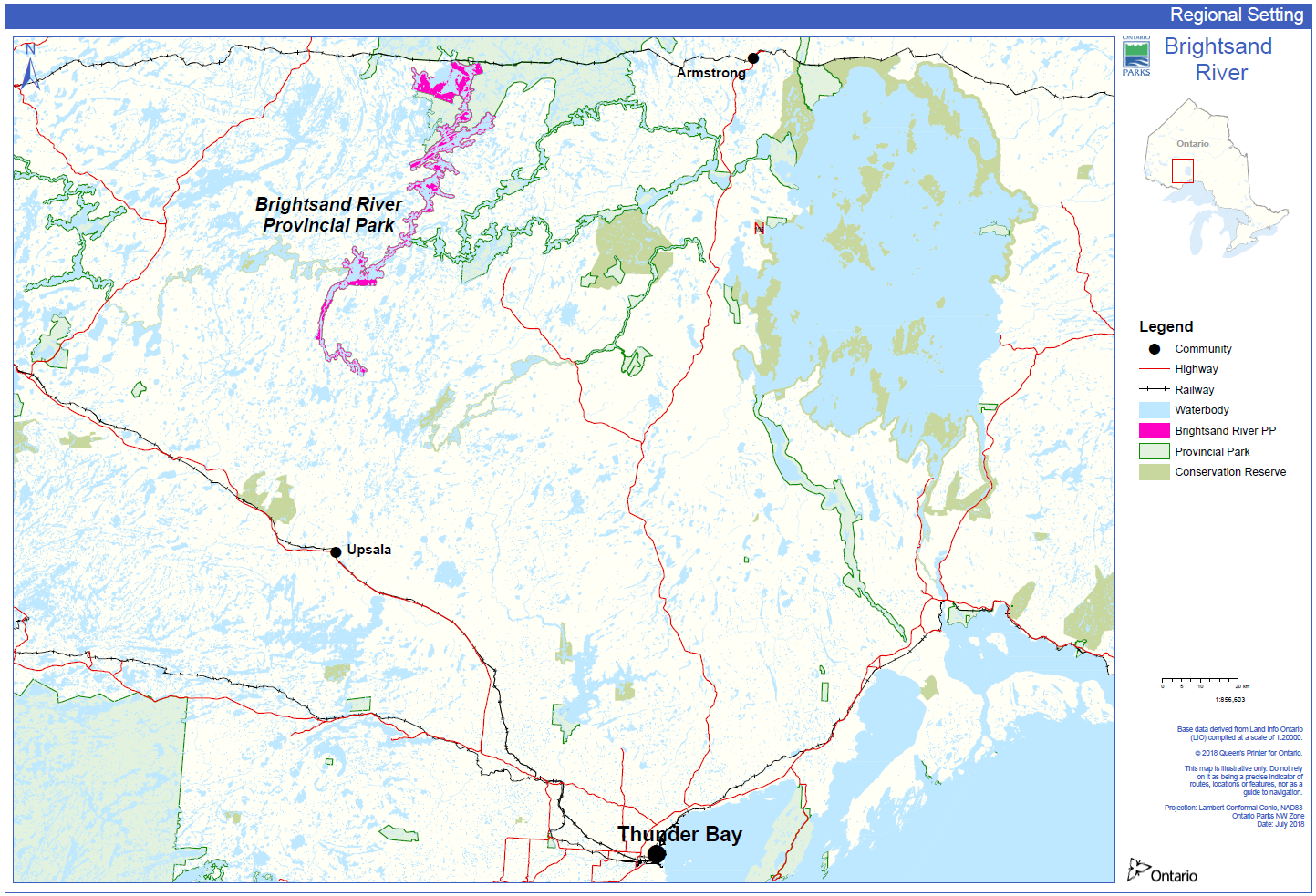

Brightsand River Provincial Park is a 41,250 ha waterway class park located 150 km (by air) northwest of Thunder Bay. The site was visited in June by Ontario Parks staff, who conducted an inventory of natural science features of this protected area.

Natural science field studies are important for observing ecological conditions and increasing the understanding of the natural resources within Ontario Parks.

King of the dragonflies

The Dragonhunter often hunts other dragonflies. When prey is taken, it is eaten headfirst!

This dragonfly also consumes other large insects (moths and butterflies). The exuviae (empty larval shell) seen in the photo below is fairly distinctive with its large, fan-shaped abdomen.

An ancient history on the planet

Dragonflies are known to be one of the first winged insects to evolve some 300 million years ago! They belong to an order called Odonata or “toothy ones.”

Like most other insects, they have a head with two antennae, a thorax bearing six legs and four wings, and an abdomen. Their life begins as an egg, laid in or near water. These eggs hatch into aquatic larvae and it is in this stage where dragonflies spend most of their lives.

From larvae to dragonfly — the emergence

Depending on the species, the aquatic stage can range from a few months to four years or longer. When larvae are mature, they make their way to the water’s edge and crawl out onto rocks, logs, emergent structures (e.g. docks) or the shoreline itself.

Once anchored on the shoreline, the larvae “bursts” open and the adult dragonfly emerges from within the larvae. When they first emerge, they will have a crinkled wing mass and short body. From here, the transformation happens fairly rapidly, and within 30 minutes or so, the wings are “pumped” up with hemolymph (insect blood) and their body grows to its full size.

They can then fly to shelter to dry and harden over the next several hours to days. An emerging dragonfly is very vulnerable during this time, as it can’t escape predation from frogs or birds.

Dragonflies in the sky

There are more than 5,000 species of dragonflies in the world, and of those about 130 species have been recorded in Ontario. Adult dragonflies have a relatively short life-span in relation to the larvae.

Whereas larvae can live upwards of four years, adult dragonflies have, on average, four to six weeks to mature, feed, find a mate, reproduce and lay eggs for the next generation.

Fearsome and skilled predator

Dragonflies have two sets of wings so they can fly straight up or down, go backwards, fly upside down and hover to pursue and capture prey. In addition, they have nearly 360-degree vision which allows them to detect and quickly hunt down their food.

Dragonflies are great hunters in both their larval and adult life. In their larval stage, they live in the water and eat anything that comes near them, including aquatic insects, tadpoles and small fish. In fact, dragonfly larvae are usually the top carnivores in freshwater habitats without fish!

As adults, they eat flies, mosquitoes, grasshoppers, butterflies, flying ants and even other dragonflies, which they catch while they’re in flight.

Formidable adversaries

Dragonfly larvae and adults are themselves a food source for other animals. Nymphs are preyed upon by fish and amphibians, whereas the adults are taken by a variety of birds, including Rusty Blackbirds, which were observed on the Brightsand River flying back and forth along the shoreline picking off dragonflies to feed their young.

Odonates are under threat not only across Ontario, but further afield as well. Climate change may be one of the most significant factors in reducing odonate populations. Drought causes shallow ponds to dry out and when these sites are dry for several years, their odonate fauna will disappear.

Not only has drought become more frequent, but also heavy rains have as well, and streams are always at risk of being reamed out by floods. Fast-moving water can scour a river-bed, removing silt and sand essential to larval habitat. Rising water can wipe out emerging individuals.

Science to the rescue!

That’s where surveys, such as those conducted by Ontario Parks, are vital to our understanding of the distribution and habitat preference of our dragonfly and damselfly populations.

Studying odonates not only provides important scientific data, but it is also a fascinating pastime!